“Coppélia”

Bolshoi Ballet

Bolshoi Theatre (New Stage)

Moscow, Russia

February 21, 2026 (evening performance)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2026 by Ilona Landgraf

My hopes on a new video release were raised when I noticed the cameraman at the Bolshoi Ballet’s performance of Coppélia, until he explained that the recording was for internal use only. It’ll set the bar high for future generations of dancers.

My hopes on a new video release were raised when I noticed the cameraman at the Bolshoi Ballet’s performance of Coppélia, until he explained that the recording was for internal use only. It’ll set the bar high for future generations of dancers.

Sergei Vikharev’s production, which he said is the most complete and exact rendition of what Nicholas Sergeyev noted from his St. Petersburg memories (his manuscripts are stored at Harvard University), has been in the Bolshoi’s repertory since 2009. It preserves all the details that fell victim to artistic, financial, and producing conditions in many Western stagings. As designated by the original creators, Marius Petipa and Enrico Cecchetti, the Bolshoi’s Swanilda has eight girlfriends, and Act III’s Waltz of the Hours is danced by twenty-four ballerinas, one for each hour of the day.  The order of their four lines of six dancers each (which represent dawn, morning, twilight, and night) is overseen by the old, bearded Chronos (Dmitry Grishin), who rests atop a huge clock that has to stand exactly center stage. The Royal Ballet’s Coppélia, by comparison, employs only eight dancers in the waltz, which subverts the scene’s meaning.

The order of their four lines of six dancers each (which represent dawn, morning, twilight, and night) is overseen by the old, bearded Chronos (Dmitry Grishin), who rests atop a huge clock that has to stand exactly center stage. The Royal Ballet’s Coppélia, by comparison, employs only eight dancers in the waltz, which subverts the scene’s meaning.

Each time I see a performance of Coppélia at the Bolshoi, the artistic director, Makhar Vaziev, is in the rear auditorium during Act III’s Fete of the Bell, his eyes scrutinizing the corps’ unity, the clarity of its patterns, and the purity of the variations. As tiny as they may be, he usually finds details to hone.

The leading couple, Swanilda (Elizaveta Kokoreva) and Frantz (Denis Zakharov), had nothing to perfect. Each step, each port de  bras, each jump, and each turn of Kokoreva represented the ideal of classical ballet and was imbued with meaning. Her acting was fresh and convincing, her pantomime unambiguous, and the show she delivered at Coppélius’s (Gennady Yanin) workshop terrific. Her fiancé, Frantz, was an unreliable lover, though. Once unobserved, he eagerly climbed through another sweetheart’s (i.e., Coppélia’s (Maria Rasskazova)) balcony door. Worse, even as he was caught red-handed by Coppélius, he affirmed his intention to marry her. What a wretch of a swain!

bras, each jump, and each turn of Kokoreva represented the ideal of classical ballet and was imbued with meaning. Her acting was fresh and convincing, her pantomime unambiguous, and the show she delivered at Coppélius’s (Gennady Yanin) workshop terrific. Her fiancé, Frantz, was an unreliable lover, though. Once unobserved, he eagerly climbed through another sweetheart’s (i.e., Coppélia’s (Maria Rasskazova)) balcony door. Worse, even as he was caught red-handed by Coppélius, he affirmed his intention to marry her. What a wretch of a swain!

Only after Swanilda got him off the hook from Coppélius’s alchemic experiments did Frantz man up. His time had come for their wedding pas de deux, with both dressed in majestic red and the cleanest of white and with jewels sparkling at Swanilda’s décolleté and in her tiara (costumes by Tatiana Noginova). A brilliant solo, including spick and span legwork and pinpoint landings, testified to Frantz’s qualities. A gem of a woman, Swanilda sped through pirouettes, landed from split jumps in stupendous balances, and masterfully played with the tempo, smiling all the while, as if excelling on stage was exactly what she relished most. The beauty that Kokoreva and Zakharov brought to life was the performance’s most precious takeaway.

Only after Swanilda got him off the hook from Coppélius’s alchemic experiments did Frantz man up. His time had come for their wedding pas de deux, with both dressed in majestic red and the cleanest of white and with jewels sparkling at Swanilda’s décolleté and in her tiara (costumes by Tatiana Noginova). A brilliant solo, including spick and span legwork and pinpoint landings, testified to Frantz’s qualities. A gem of a woman, Swanilda sped through pirouettes, landed from split jumps in stupendous balances, and masterfully played with the tempo, smiling all the while, as if excelling on stage was exactly what she relished most. The beauty that Kokoreva and Zakharov brought to life was the performance’s most precious takeaway.

In Act III, Elizaveta Kruteleva’s L’Aurore solo became more fluid over time as if warmed by the rising sun. Antonina Chapkina delivered a solemn, graceful La Prière solo, and Ekaterina Varlamova a zippy one as Folie. Maria Mishina led the pas de cinq Le Travail. The corps’ czardas and mazurka had verve, and Swanilda’s friends seemed ready to follow in her footsteps.

In Act III, Elizaveta Kruteleva’s L’Aurore solo became more fluid over time as if warmed by the rising sun. Antonina Chapkina delivered a solemn, graceful La Prière solo, and Ekaterina Varlamova a zippy one as Folie. Maria Mishina led the pas de cinq Le Travail. The corps’ czardas and mazurka had verve, and Swanilda’s friends seemed ready to follow in her footsteps.

The orchestra of the Bolshoi Theatre played under the baton of Pavel Klinichev. Their rendition of Leo Delibes’s score was vibrant, creamy, and perfectly in tune with the dancers.

| Link: | Website of the Bolshoi Theatre | |

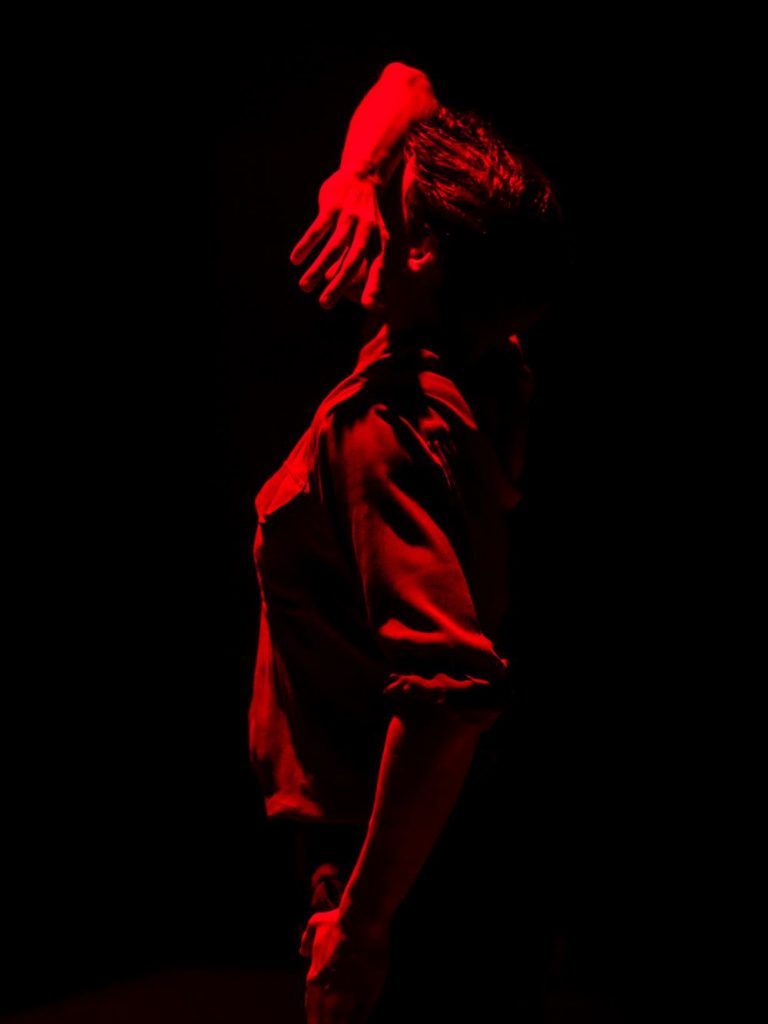

| Photos: | 1. | Elizaveta Kokoreva (Swanilda) and Denis Zakharov (Frantz), “Coppélia” by Sergei Vikharev after Marius Petipa and Enrico Cecchetti, Bolshoi Ballet 2026 |

| 2. | Denis Zakharov (Frantz), Elizaveta Kokoreva (Swanilda), and ensemble; “Coppélia” by Sergei Vikharev after Marius Petipa and Enrico Cecchetti, Bolshoi Ballet 2026 | |

| 3. | Elizaveta Kokoreva (Swanilda) and Denis Zakharov (Frantz), “Coppélia” by Sergei Vikharev after Marius Petipa and Enrico Cecchetti, Bolshoi Ballet 2026 | |

| 4. | Elizaveta Kokoreva (Swanilda) and ensemble, “Coppélia” by Sergei Vikharev after Marius Petipa and Enrico Cecchetti, Bolshoi Ballet 2026 | |

| 5. | Elizaveta Kokoreva (Swanilda), Denis Zakharov (Frantz), and ensemble; “Coppélia” by Sergei Vikharev after Marius Petipa and Enrico Cecchetti, Bolshoi Ballet 2026 |

|

| all photos © Bolshoi Theatre/Pavel Rychkov | ||

| Editing: | Kayla Kauffman |