“Forever Young”

Bavarian State Ballet

National Theater

Munich, Germany

February 01, 2014

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2014 by Ilona Landgraf

“Forever young”, claims the Bavarian State Ballet, are the pieces on this eponymous triple bill, which premiered last season. At least two of them – “The Moor’s Pavane”, choreographed in 1949 by modern dance icon José Limón, and “Choreartium”, choreographed in 1933 by Léonide Massine – are said to be masterpieces exempt from aging. The third, Russell Maliphant’s “Broken Fall”, dating from 2003, has yet to prove its endurance.

“Forever young”, claims the Bavarian State Ballet, are the pieces on this eponymous triple bill, which premiered last season. At least two of them – “The Moor’s Pavane”, choreographed in 1949 by modern dance icon José Limón, and “Choreartium”, choreographed in 1933 by Léonide Massine – are said to be masterpieces exempt from aging. The third, Russell Maliphant’s “Broken Fall”, dating from 2003, has yet to prove its endurance.

The evening started with the contemporary “Broken Fall” and turned back along the timeline to the modernist classics. Created for the Royal Ballet, or more precisely for Sylvie Guillem, the Maliphant work toys with gravity and the risk of falling by challenging the body control of three dancers. It tests the limits of mutual trust. Set to artificial soundscapes by Berry Adamson, the atmosphere was slightly surreal. Two men and one woman – Matej Urban, Nikita Korotkov and Ekaterina Petina -, bare foot and clad in shorts and simple tops, gave little samples of their abilities in passing. They seemed cool professionals engaged in casual training. Their interactions began with slow motion lifts and counterbalances, the interactions becoming more and more risky. Petina’s knee pads seemed to proclaim that, in the sports context, no hazard would be avoided. The three dancers’ faces were, aptly, serious throughout. Although the dancing had the appearance of contact improvisation, it lacked spontaneity and play. Everything was too well-calculated. Lifts and falls were audacious, yet all motion had a smooth quality with the transitions, especially, being softened. Consequently, the interaction of strongly contrasting forces was pretty much watered down. What we got was a physical gymnastics demonstration. Petina, in her final solo which included some classical dance vocabulary, had feline strength, radiated power and was expressive – more so than anything preceding this display.

Limòn’s “The Moor’s Pavane” deals with the core plot of Shakespeare’s tragedy “Othello”. The four leading figures – Othello, Desdemona, Iago and Emilia – enact the story’s crucial moments in less than twenty minutes. It all starts with Othello giving the handkerchief to Desdemona. However, Limón does not label his characters with their original names from Shakespeare’s play. Rather he broadened the piece’s meaning to show basic emotions such as love, tenderness and abysmal malice, pride and destructive jealousy. “The Moor’s Pavane” was thought to be his comment on the intrigues, defamations and hysteria of America’s McCarthy era. Next to the Moore (Léonard Engel) there’s his wife (Séverine Ferrolier), his friend (Lukáš Slavický) and the friend’s wife (Emma Barrowman). The pavane – a processional popular with 16th and 17th century aristocrats – has a strict formality that limits expressivity through movement. Center stage, as hub, was the quartet of characters. Everything started and ended with that quartet formation. The choreographic form as well as the costume design and light design – evoking an intimate play’s atmosphere – were inspired by Renaissance architecture and painting. Velvet fabrics and unicolor dresses sumptuously billowing, yet heavy, and floor-length made for the piece’s weightiness and grounding which was palpable as soon as the curtain rose. The music of Henry Purcell (“The Gordian Knot Untied” and “Abdelazer or The Moor’s Revenge”) had been arranged by Simon Sadoff.

Limòn’s “The Moor’s Pavane” deals with the core plot of Shakespeare’s tragedy “Othello”. The four leading figures – Othello, Desdemona, Iago and Emilia – enact the story’s crucial moments in less than twenty minutes. It all starts with Othello giving the handkerchief to Desdemona. However, Limón does not label his characters with their original names from Shakespeare’s play. Rather he broadened the piece’s meaning to show basic emotions such as love, tenderness and abysmal malice, pride and destructive jealousy. “The Moor’s Pavane” was thought to be his comment on the intrigues, defamations and hysteria of America’s McCarthy era. Next to the Moore (Léonard Engel) there’s his wife (Séverine Ferrolier), his friend (Lukáš Slavický) and the friend’s wife (Emma Barrowman). The pavane – a processional popular with 16th and 17th century aristocrats – has a strict formality that limits expressivity through movement. Center stage, as hub, was the quartet of characters. Everything started and ended with that quartet formation. The choreographic form as well as the costume design and light design – evoking an intimate play’s atmosphere – were inspired by Renaissance architecture and painting. Velvet fabrics and unicolor dresses sumptuously billowing, yet heavy, and floor-length made for the piece’s weightiness and grounding which was palpable as soon as the curtain rose. The music of Henry Purcell (“The Gordian Knot Untied” and “Abdelazer or The Moor’s Revenge”) had been arranged by Simon Sadoff.

Ferrollier portrayed an innocent, pure and a bit pale Desdemona, while Barrowman’s blond-braided Emilia was obviously so naive not to know at the end how things had happened and what part she had played in the disaster. In Slavický’s characterization of Iago I missed a clear psychological profile. What had stung him to intrigue remained vague. Because of the formal structure every step, gesture and glance is the condensate of strong emotions and thus has highly

Ferrollier portrayed an innocent, pure and a bit pale Desdemona, while Barrowman’s blond-braided Emilia was obviously so naive not to know at the end how things had happened and what part she had played in the disaster. In Slavický’s characterization of Iago I missed a clear psychological profile. What had stung him to intrigue remained vague. Because of the formal structure every step, gesture and glance is the condensate of strong emotions and thus has highly  concentrated meaning. Engel as ‘The Moor’, for example, desperately raised his arm when facing his murdered wife. He entirely fulfilled the form – dramatically splayed hands, horror in the face – but failed to give his acting powerful internal meaning. In fact the challenge would have been to focus the spectator’s attention like a zoom lens on each gesture what only works when being utmost present and thus expressive.

concentrated meaning. Engel as ‘The Moor’, for example, desperately raised his arm when facing his murdered wife. He entirely fulfilled the form – dramatically splayed hands, horror in the face – but failed to give his acting powerful internal meaning. In fact the challenge would have been to focus the spectator’s attention like a zoom lens on each gesture what only works when being utmost present and thus expressive.

The playbill, actually almost a little book, provided by Bavarian State Ballet, proved to be a treasure chest for valuable background information and not only in the case of “The Moor’s Pavane”. Now previously unpublished notes on the characters, casting and scenes by Limón’s longtime assistant Sarah Stackhouse, who had been Munich’s répétiteur for “The Moor’s Pavane”, generously provide backstage insights.

“Choreartium” danced to Johannes Brahms’ Fourth Symphony, with which the evening closed, has a completely different, almost diametrically opposed, choreographic approach. Movements have to be fluid and without any breaks as if the dancers breathe the music. Being Massine’s second attempt to choreograph a symphony – his first had been “Les Présages” to Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony also in 1933 – he intended to focus even more on an abstract interpretation. The premiere in London with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo caused a scandal: Symphonies were thought as autarkic, untouchable sanctuaries and thus were definitely taboo for any appropriation by dance! A collection of historical newspaper articles in the playbill, originally published in “The World of Music”, gives an idea of the heated and also polemical debate between Massine’s defender, music critic Ernest Newman, and others who considered the interpretation of a symphony through ballet as sacrilege.

“Choreartium” danced to Johannes Brahms’ Fourth Symphony, with which the evening closed, has a completely different, almost diametrically opposed, choreographic approach. Movements have to be fluid and without any breaks as if the dancers breathe the music. Being Massine’s second attempt to choreograph a symphony – his first had been “Les Présages” to Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony also in 1933 – he intended to focus even more on an abstract interpretation. The premiere in London with the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo caused a scandal: Symphonies were thought as autarkic, untouchable sanctuaries and thus were definitely taboo for any appropriation by dance! A collection of historical newspaper articles in the playbill, originally published in “The World of Music”, gives an idea of the heated and also polemical debate between Massine’s defender, music critic Ernest Newman, and others who considered the interpretation of a symphony through ballet as sacrilege.

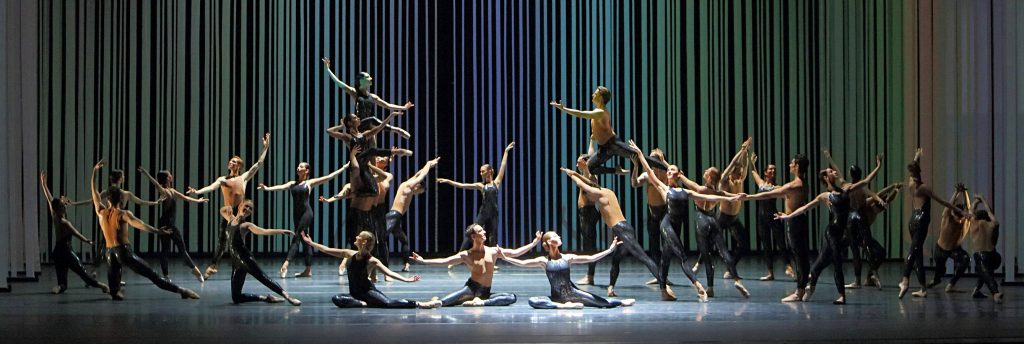

Ignoring bygone attitudes to morality and the loss of any complexion of its being revolutionary, I enjoyed “Choreartium” very much: The constantly varying structures in the buoyant first movement and the beautiful patterns of arm movements by the female corps in the second movement had a ceremonial atmosphere. The third movement was light-footed and sunny like a sorbet, yet also sophisticated due to elaborately patterned groupings. The gloomy fourth movement, which brought all dancers together again, marred my delight. Not strong jumpers, some of the men’s tour en l’airs went thoroughly wrong. Regardless of fluidity, clear shapes should have been carved out, but the men’s movements were rather blurred.

Ignoring bygone attitudes to morality and the loss of any complexion of its being revolutionary, I enjoyed “Choreartium” very much: The constantly varying structures in the buoyant first movement and the beautiful patterns of arm movements by the female corps in the second movement had a ceremonial atmosphere. The third movement was light-footed and sunny like a sorbet, yet also sophisticated due to elaborately patterned groupings. The gloomy fourth movement, which brought all dancers together again, marred my delight. Not strong jumpers, some of the men’s tour en l’airs went thoroughly wrong. Regardless of fluidity, clear shapes should have been carved out, but the men’s movements were rather blurred.

The fresh decor, commissioned by Dutchman Keso Dekker, was marvelous. He used white vertical blinds for the wings and as backdrop, which at times were partially bathed in an array of colors. The men wore skin-colored tricots and black tights with a lacy look, which shone like latex in the third and fourth movement. The women’s dresses were of the same fabric with added spots of colors: blue and mint green in the first quarter, supplemented with shades of orange and yellow in the third. Witty was the idea to introduce “Choreartium” on a video screen (title, choreographer and time of creation were displayed). All in all a highly successful transfer of a previous era’s gem to the present.

| Links: | Bavarian State Ballet’s Homepage | |

| Photos: | 1. | Nikita Korotkov and Ekaterina Petina “Broken Fall” by Russell Maliphant, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 |

| 2. | Nikita Korotkov, Ekaterina Petina and Matej Urban, “Broken Fall” by Russell Maliphant, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| 3. | Séverine Ferrolier and Léonard Engel, “The Moor’s Pavane” by José Limón, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| 4. | Emma Barrowman and Lukáš Slavický, “The Moor’s Pavane” by José Limón, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| 5. | Lukáš Slavický, Séverine Ferrolier, Emma Barrowman and Léonard Engel, “The Moor’s Pavane” by José Limón, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| 6. | Séverine Ferrolier and ensemble, “Choreartium” by Léonide Massine, 2nd movement, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| 7. | Ensemble, “Choreartium” by Léonide Massine, 2nd movement, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| 8. | Ensemble, “Choreartium” by Léonide Massine, 3rd movement, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| 9 | Ensemble, “Choreartium” by Léonide Massine, 4th movement, Forever Young, Bavarian State Ballet, Munich 2014 | |

| all photos © Wilfried Hösl 2014 | ||

| Editing: | Laurence Smelser, George Jackson |