“Snow Maiden. Myth and Reality” (“Another Light”/“Refraction”)

Ballet of the Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre

Hvorostovsky Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre

Krasnoyarsk, Russia

July 2024 (video)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2024 by Ilona Landgraf

In March last year, the Russian playwright Alexander Ostrovsky (1823-1886) would have celebrated his bicentenary. Around one hundred and fifty years ago, in September 1873, he published The Snow Maiden, a work of narrative poetry about a fairy-tale, fantasy tsardom in prehistoric times for which Tchaikovsky wrote the music. A few years later, it was adapted into an opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The Snow Maiden deals with the opposition between eternal forces of nature (represented by the mythological characters of Grandfather Frost, Spring Beauty, the Sun God Yarilo, and a wood sprite), humans (a merchant and citizens), and those in-between (half-real, half-mythological characters, like Snow Maiden and the shepherd boy, Lel). The title character, daughter of Grandfather Frost and Spring Beauty, decides to live among the people, whom her beauty enchants. She is, however, unable to feel love, which complicates her interactions with humans. After her mother grants her the ability to love, Snow Maiden’s passion for the merchant, Mizgir, is ignited. As her hearts warms and she declares her love, a bright ray of sunlight hits her and she melts. Her demise conciliates the Sun God, Yarilo, who, angered by her sheer existence, had withheld sun and warmth. Consequently, the forces of nature become rebalanced.

In March last year, the Russian playwright Alexander Ostrovsky (1823-1886) would have celebrated his bicentenary. Around one hundred and fifty years ago, in September 1873, he published The Snow Maiden, a work of narrative poetry about a fairy-tale, fantasy tsardom in prehistoric times for which Tchaikovsky wrote the music. A few years later, it was adapted into an opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. The Snow Maiden deals with the opposition between eternal forces of nature (represented by the mythological characters of Grandfather Frost, Spring Beauty, the Sun God Yarilo, and a wood sprite), humans (a merchant and citizens), and those in-between (half-real, half-mythological characters, like Snow Maiden and the shepherd boy, Lel). The title character, daughter of Grandfather Frost and Spring Beauty, decides to live among the people, whom her beauty enchants. She is, however, unable to feel love, which complicates her interactions with humans. After her mother grants her the ability to love, Snow Maiden’s passion for the merchant, Mizgir, is ignited. As her hearts warms and she declares her love, a bright ray of sunlight hits her and she melts. Her demise conciliates the Sun God, Yarilo, who, angered by her sheer existence, had withheld sun and warmth. Consequently, the forces of nature become rebalanced.

While rarely performed on Western stages, The Snow Maiden is a fixture of Russian culture. This season, on the occasion of Ostrovsky’s and his piece’s anniversary, the Bolshoi Theatre premiered a new version, and the Stanislavsky Ballet revived Vladimir Bourmeister’s 1963 choreography. Both are set to Tchaikovsky’s score. At the invitation of the DANCEINVERSION International Festival of Contemporary Dance (which is directed at the Bolshoi Theatre by Irina Chernomurova), six choreographers from all over Russia were able to realize their interpretations of Ostrovsky’s fairy tale. Two of them—Irina Kononova and Alyona Britvak—worked with the Krasnoyarsk Ballet. Their one-act ballets premiered in March as part of the double bill, Snow Maiden. Myth and Reality.

While rarely performed on Western stages, The Snow Maiden is a fixture of Russian culture. This season, on the occasion of Ostrovsky’s and his piece’s anniversary, the Bolshoi Theatre premiered a new version, and the Stanislavsky Ballet revived Vladimir Bourmeister’s 1963 choreography. Both are set to Tchaikovsky’s score. At the invitation of the DANCEINVERSION International Festival of Contemporary Dance (which is directed at the Bolshoi Theatre by Irina Chernomurova), six choreographers from all over Russia were able to realize their interpretations of Ostrovsky’s fairy tale. Two of them—Irina Kononova and Alyona Britvak—worked with the Krasnoyarsk Ballet. Their one-act ballets premiered in March as part of the double bill, Snow Maiden. Myth and Reality.

Irina Kononova is the director and choreographer of 10th Dance Avenue in Stavropol, North Caucasus. Her Another Light fast forwards The Snow Maiden into a future of a bewildered, divine realm where humans have regressed to animalistic behaviors and where the rest of the world is generated by artificial intelligence. The piece is strange but bold and, I’m afraid, has a finger on the pulse.

Irina Kononova is the director and choreographer of 10th Dance Avenue in Stavropol, North Caucasus. Her Another Light fast forwards The Snow Maiden into a future of a bewildered, divine realm where humans have regressed to animalistic behaviors and where the rest of the world is generated by artificial intelligence. The piece is strange but bold and, I’m afraid, has a finger on the pulse.

The three worlds that set designer, Ulyana Eremina, layered were reminiscent of a Mondrian painting. A rectangular video screen hanging center stage displayed Snow Maiden’s white world. It showed an artificial, infinite realm (visual content by Oleg Lyubimov) where Snow Maiden (Nadezhda Vagal) saw her psychologist. Below the screen, on the ground, dark-clad people inhabited a foggy, gloomy world. Toxic green and fiery orange lighting gave it a hellish appearance. A door and a (moveable) staircase connected the people to the white world above, but the gateway was reserved for Snow Maiden and the Sun God, Yarilo (Yury Kudryavtsev).

Yarilo, a weird, androgynous figure with an orange-red bob, wore a suit in the same color. He (or she?) reigned on top, in a small, rectangular, red, video world above the white realm but decided to check in on Snow Maiden. Gradually descending into lower spheres, Yarilo first bellyflopped quite clumsily into Snow Maiden’s therapy session and then, baffled by the setting, snuck down the staircase into the people-inhabited lowland. Though he brought warm light, the people remained motionless, like hypothermic reptiles. Lel (Konstantin Polkovnikov) and Mizgir (Nikita Lysenko) were among them but remained anonymous. One group was frozen to a four-head installation; five others hunched around the plexiglass silhouette of a human body—presumably Snow Maiden’s—which resembled a chalk body outline at a crime scene. (The plexiglass silhouette was later filled with water, indicating that Snow Maiden was melting away.)

Yarilo, a weird, androgynous figure with an orange-red bob, wore a suit in the same color. He (or she?) reigned on top, in a small, rectangular, red, video world above the white realm but decided to check in on Snow Maiden. Gradually descending into lower spheres, Yarilo first bellyflopped quite clumsily into Snow Maiden’s therapy session and then, baffled by the setting, snuck down the staircase into the people-inhabited lowland. Though he brought warm light, the people remained motionless, like hypothermic reptiles. Lel (Konstantin Polkovnikov) and Mizgir (Nikita Lysenko) were among them but remained anonymous. One group was frozen to a four-head installation; five others hunched around the plexiglass silhouette of a human body—presumably Snow Maiden’s—which resembled a chalk body outline at a crime scene. (The plexiglass silhouette was later filled with water, indicating that Snow Maiden was melting away.)

The sight of the people literally floored Yarilo and, like a flustered chicken, he quickly hopped back into the white world but couldn’t ascend further because his red home realm had moved away. He later witnessed Snow Maiden’s encounter with the people and her demise, which unhinged and exhausted him enough to seek help from the therapist himself. (The creamy, white substance that the therapist squeezed between her fingers while gloating might have been the memories that she pressed out of Yarilo’s brain.)

Snow Maiden fluttered down to the people like an innocent, white butterfly. She was the sensitive one, running against frighteningly dumb and inarticulate creatures who moved on both legs or all fours like apes or jerked their heads rhythmically back and forth. Oleg Lyubimov’s electro-acoustic sound of tight metal machinery was fraught with tension and fitted their characters. Soon, only fragments of Snow Maiden’s initial beauty were left, but she stayed with the people, who tore at her limbs as if she were a straw doll that could be ripped apart. Though the squishy, frog pond-like sounds that accompanied her death indicated a new beginning, the people behaved as retarded as before. Mizgir stood aloof, his shoulders hunched, his gaze bland, shaken by hiccup-like convulsions. Enlightenment seemed far away.

Snow Maiden fluttered down to the people like an innocent, white butterfly. She was the sensitive one, running against frighteningly dumb and inarticulate creatures who moved on both legs or all fours like apes or jerked their heads rhythmically back and forth. Oleg Lyubimov’s electro-acoustic sound of tight metal machinery was fraught with tension and fitted their characters. Soon, only fragments of Snow Maiden’s initial beauty were left, but she stayed with the people, who tore at her limbs as if she were a straw doll that could be ripped apart. Though the squishy, frog pond-like sounds that accompanied her death indicated a new beginning, the people behaved as retarded as before. Mizgir stood aloof, his shoulders hunched, his gaze bland, shaken by hiccup-like convulsions. Enlightenment seemed far away.

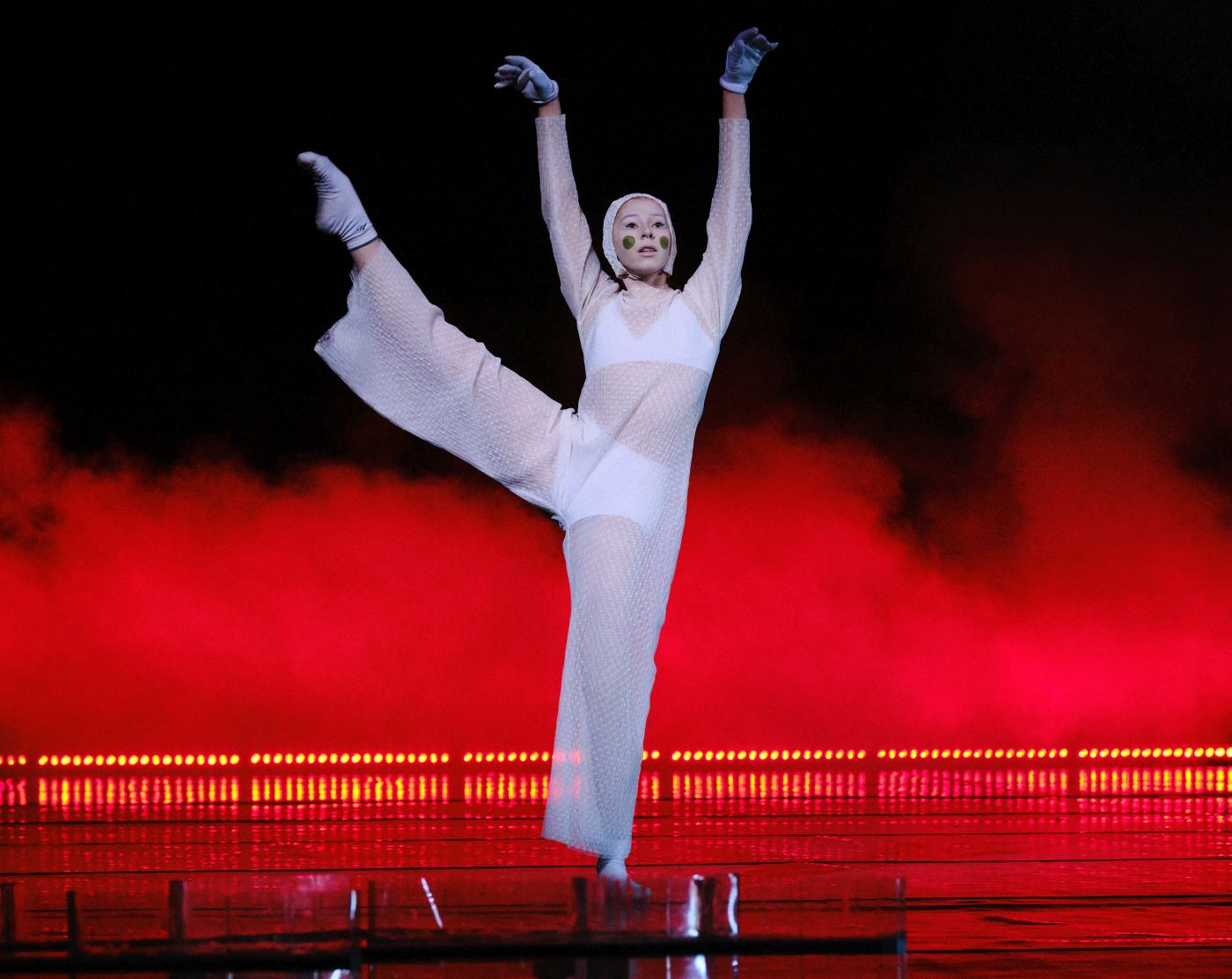

Alyona Britvak came to choreography by a sinuous route and is currently enrolled in a master’s program for dance at St. Petersburg’s Vaganova Academy. Her three-part ballet, Refraction, contains explicit language. It focuses on Snow Maiden (Elena Mikheecheva), her mother Spring (Olesya Aldonina), and Lel (Matvey Nikishaev), who is not a shepherd but a visual artist.

Alyona Britvak came to choreography by a sinuous route and is currently enrolled in a master’s program for dance at St. Petersburg’s Vaganova Academy. Her three-part ballet, Refraction, contains explicit language. It focuses on Snow Maiden (Elena Mikheecheva), her mother Spring (Olesya Aldonina), and Lel (Matvey Nikishaev), who is not a shepherd but a visual artist.

As in Another Light, the mythological character, in this case Spring, wore a red costume (costume design by Olga Kravtsova). She reflected upon herself in front of a mirror in an extended solo set to a mix of silence and an atmospheric, electronic soundscape (music by Andreas Moustoukis). Unmistakable movements highlighted the goings on; Spring’s hand on her belly signaled her wish to become pregnant; her raised arm (accompanied by the sound of a bell) indicated conception; when her movements became cumbersome, it was clear that Snow Maiden’s birth was imminent.

Overflowing with maternal love, Spring examined and watched over each stirring of her daughter, who inevitably became her copy. Yet, Snow Maiden’s mind began to balk. Her mother doubled down, using the sleeves of her daughter’s dress as strings to manipulate her like a puppet.

Overflowing with maternal love, Spring examined and watched over each stirring of her daughter, who inevitably became her copy. Yet, Snow Maiden’s mind began to balk. Her mother doubled down, using the sleeves of her daughter’s dress as strings to manipulate her like a puppet.

The appearance of Lel, whose inner life found expression in art (each emotion resulted in a splash of color), helped Snow Maiden to free herself from her mother’s prison (represented by a plexiglass box). Snow Maiden subsequently joined Lel’s artistic community, which revolved around their sculptures, among them a snail shell, a ram’s head, and a fish-like object.

They moved in sync as one entity, hopped around wildly, and marched in line like blind people, one hand resting on the shoulder of the person in front. Lel’s interest in Snow Maiden was superficial and short-lived. As she tried to become part of the group’s bizarre living art installation, Lel pushed her aside.

They moved in sync as one entity, hopped around wildly, and marched in line like blind people, one hand resting on the shoulder of the person in front. Lel’s interest in Snow Maiden was superficial and short-lived. As she tried to become part of the group’s bizarre living art installation, Lel pushed her aside.

In the final scene, Snow Maiden glanced in the mirror and seemingly became self-aware. Her wide, swinging arms gently dissolved the installation, and the artists suddenly obeyed her every move. A featureless group with soft, non-descript movements, they lifted her like a cherished icon before dispersing. Lel eventually knelt ruefully at Snow Maiden’s feet, and Snow Maiden decided to stay with him and abandon her mother.

| Links: | Website of the Hvorostovsky Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre | |

| “The Snow Maiden. Myth and Reality” – TC Yenisei, Nasha Kultura | ||

| A New Variation of “The Snow Maiden” – TC Prima | ||

| Krasnoyarsk Opera and Ballet Theatre is preparing an updated “Snow Maiden” – Vesti | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Portrait of Alexander Ostrovsky by Vasily Perov, 1871 |

| 2. | Book cover of Alexander Ostrovsky’s “The Snow Maiden” |

|

| 3. | Ensemble, “Another Light” by Irina Kononova, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 4. | Yury Kudryavtsev (Yarilo) and ensemble, “Another Light” by Irina Kononova, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 5. | Ensemble, “Another Light” by Irina Kononova, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 6. | Denis Kazarin (Tsar Berendey), Konstantin Polkovnikov (Lel), and Nadezhda Panfilova (Kupava), “Another Light” by Irina Kononova, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 7. | Yury Kudryavtsev (Yarilo) and Nadezhda Vagal (Snow Maiden), “Another Light” by Irina Kononova, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 8. | Nadezhda Vagal (Snow Maiden), “Another Light” by Irina Kononova, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 9. | Olesya Aldonina (Spring), “Refraction” by Alyona Britvak, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 10. | Elena Mikheecheva (Snow Maiden) and Olesya Aldonina (Spring), “Refraction” by Alyona Britvak, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 |

|

| 11. | Matvey Nikishaev (Lel), “Refraction” by Alyona Britvak, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 |

|

| 12. | Matvey Nikishaev (Lel) and Elena Mikheecheva (Snow Maiden), “Refraction” by Alyona Britvak, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 13. | Elena Mikheecheva (Snow Maiden) and ensemble, “Refraction” by Alyona Britvak, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 |

|

| 14. | Elena Mikheecheva (Snow Maiden), Olesya Aldonina (Spring), and ensemble, “Refraction” by Alyona Britvak, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| 15. | Elena Mikheecheva (Snow Maiden), “Refraction” by Alyona Britvak, Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 | |

| all photos by Evgeny Koryukin © Krasnoyarsk State Opera and Ballet Theatre 2024 |

||

| Editing: | Kayla Kauffman |