“Oscar©”

The Australian Ballet

Sydney Opera House/Joan Sutherland Theatre

Sydney, Australia

November 19, 2024 (live stream)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2024 by Ilona Landgraf

One long year has passed since The Australian Ballet’s last live stream, and it was uncertain if the company would dance again for an online audience. But after moving from Melbourne’s State Theatre (which is closed for major renovations) to their temporary home at the nearby Regent Theatre, they are back online. Christopher Wheeldon’s Oscar© was the first ballet streamed live from the Sydney Opera House. Moreover, it is the first full-length commission by artistic director, David Hallberg, who has been friends with Wheeldon for twenty years. As a choreographer, Wheeldon is “hot property,” Hallberg stated. Oscar© combines biographical aspects of the well-known, yet divisive, Irish author Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) with two pieces of his oeuvre.

One long year has passed since The Australian Ballet’s last live stream, and it was uncertain if the company would dance again for an online audience. But after moving from Melbourne’s State Theatre (which is closed for major renovations) to their temporary home at the nearby Regent Theatre, they are back online. Christopher Wheeldon’s Oscar© was the first ballet streamed live from the Sydney Opera House. Moreover, it is the first full-length commission by artistic director, David Hallberg, who has been friends with Wheeldon for twenty years. As a choreographer, Wheeldon is “hot property,” Hallberg stated. Oscar© combines biographical aspects of the well-known, yet divisive, Irish author Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) with two pieces of his oeuvre.

As usual, Hallberg and presenter Catherine Murphy co-hosted the live stream, conducting backstage interviews and chatting about the piece. Hallberg quickly made clear that when approaching Wheeldon, he had a bold, unapologetic story in mind that wouldn’t shy away from telling uncomfortable realities, such as Wilde’s homosexuality for which he was persecuted and sentenced to two years in prison. As Wilde was married and had two sons, he was bisexual, though this classification wasn’t common in Victorian England.

Hallberg and Wheeldon agreed that Wilde’s struggle relates to that of contemporary queer people (which they consider themselves to be) and that they hoped Oscar© would persuade the audience to be more accepting. “There’s a lack of representation of queer stories in narrative ballet,” Hallberg explained. “There was always the prince and the princess…and now we really feel that the conversation is changing, and it’s really important that people can recognize themselves on stage that aren’t just the prince and the princess…I had to play the prince for twenty years, I had to play Romeo for twenty years…I loved every minute, but I didn’t see myself on stage. And so I feel this is such an important moment for the company, for the ballet world, to have more inclusivity of representation on stage.” Although he didn’t say it explicitly, it was obvious that the moment was, above all, important for him.

Hallberg and Wheeldon agreed that Wilde’s struggle relates to that of contemporary queer people (which they consider themselves to be) and that they hoped Oscar© would persuade the audience to be more accepting. “There’s a lack of representation of queer stories in narrative ballet,” Hallberg explained. “There was always the prince and the princess…and now we really feel that the conversation is changing, and it’s really important that people can recognize themselves on stage that aren’t just the prince and the princess…I had to play the prince for twenty years, I had to play Romeo for twenty years…I loved every minute, but I didn’t see myself on stage. And so I feel this is such an important moment for the company, for the ballet world, to have more inclusivity of representation on stage.” Although he didn’t say it explicitly, it was obvious that the moment was, above all, important for him.

To back Oscar© with a solid footing, the company intensified its longstanding partnership with Melbourne’s La Trobe University whose experts provided the social context of Oscar Wilde’s life. Their research about life—especially queer life—in Victorian-era London was implemented in a workshop with the dancers and turned into the book, The Importance of Being Oscar. During their one-year preparation, the dancers also worked with intimacy coordinator Amy Cater to ensure that everyone felt safe while performing sensually heated choreography, which Wheeldon included in abundance.

To back Oscar© with a solid footing, the company intensified its longstanding partnership with Melbourne’s La Trobe University whose experts provided the social context of Oscar Wilde’s life. Their research about life—especially queer life—in Victorian-era London was implemented in a workshop with the dancers and turned into the book, The Importance of Being Oscar. During their one-year preparation, the dancers also worked with intimacy coordinator Amy Cater to ensure that everyone felt safe while performing sensually heated choreography, which Wheeldon included in abundance.

The two-act ballet opened with Wilde’s trial in 1895 and his imprisonment. While in reality he was detained in three different prisons in London, his onstage cell was built in the likeness of Reading Gaol, a prison west of London where he was moved to in November 1895. Mulling over his past, Wilde (at that time merely registered as prisoner C.3.3) remembered his happy family life, his admiration for actresses, and how he enjoyed the adulation of upper-class social circles for  his literary genius. His thoughts went back to his first encounter with the seventeen-year-old Robbie Ross who was determined to seduce him and became his first male lover. Behind the back of Wilde’s wife, Constance—who was either clueless or turned a blind eye to her husband’s activities—Ross introduced Wilde to London’s queer scene where his homosexuality burgeoned. Recollections of his writing merged with these memories. In Act I, Wilde remembered scenes of The Nightingale and the Rose (1888); in Act II, he thought back to The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890/91) and, acting as Gray’s gradually uglified portrait, became part of the novel. In Act II, Wilde had served nearly his full prison term (the tally chart on the front curtain counted 722 days). Harsh detention conditions had ruined his health, and a chronic middle ear infection (which would lead to his death) tormented him. As his memories drifted, he recalled his intense romance with Lord Alfred Douglas (also known as Bosie), which later turned into a nasty power play, and sexual excesses that increasingly resembled an orgy in hell. Tortured by pain and hunger, Wilde’s thoughts jumped from Dorian Gray (who, brimming with ire, stabbed the painter Basil Hallward to death and cut up his portrait) to his own trial where he imagined himself standing on the dock, flanked by shadow plays of homosexual sex and charged by his wife.

his literary genius. His thoughts went back to his first encounter with the seventeen-year-old Robbie Ross who was determined to seduce him and became his first male lover. Behind the back of Wilde’s wife, Constance—who was either clueless or turned a blind eye to her husband’s activities—Ross introduced Wilde to London’s queer scene where his homosexuality burgeoned. Recollections of his writing merged with these memories. In Act I, Wilde remembered scenes of The Nightingale and the Rose (1888); in Act II, he thought back to The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890/91) and, acting as Gray’s gradually uglified portrait, became part of the novel. In Act II, Wilde had served nearly his full prison term (the tally chart on the front curtain counted 722 days). Harsh detention conditions had ruined his health, and a chronic middle ear infection (which would lead to his death) tormented him. As his memories drifted, he recalled his intense romance with Lord Alfred Douglas (also known as Bosie), which later turned into a nasty power play, and sexual excesses that increasingly resembled an orgy in hell. Tortured by pain and hunger, Wilde’s thoughts jumped from Dorian Gray (who, brimming with ire, stabbed the painter Basil Hallward to death and cut up his portrait) to his own trial where he imagined himself standing on the dock, flanked by shadow plays of homosexual sex and charged by his wife.

To broaden the context, Wheeldon included a narrator (Seán O’Shea) who provided background information about Wilde’s life in the prologue. He commented on goings-on a few times and returned in the epilogue (when Robbie Ross led Wilde out of prison upon his release) to recite the sonnet that Bosie had written for Wilde. The moment O’Shea declaimed its last line, “and knew that he was dead,” the on-stage Wilde met the nightingale of his fairy tale. In the fairy tale, it sacrificed itself for a principle of love that the main female figure didn’t share. Literary history says that Wilde regretted his former lifestyle in the years before his death. Wheeldon had the nightingale tenderly care for the dead Wilde in the final scene, suggesting that this regret was genuine.

To broaden the context, Wheeldon included a narrator (Seán O’Shea) who provided background information about Wilde’s life in the prologue. He commented on goings-on a few times and returned in the epilogue (when Robbie Ross led Wilde out of prison upon his release) to recite the sonnet that Bosie had written for Wilde. The moment O’Shea declaimed its last line, “and knew that he was dead,” the on-stage Wilde met the nightingale of his fairy tale. In the fairy tale, it sacrificed itself for a principle of love that the main female figure didn’t share. Literary history says that Wilde regretted his former lifestyle in the years before his death. Wheeldon had the nightingale tenderly care for the dead Wilde in the final scene, suggesting that this regret was genuine.

As in previous productions, Wheeldon teamed up with composer Joby Talbot whose tailor-made score was played by the Opera Australia Orchestra under the baton of Jonathan Lo. Especially in Act I, its style was reminiscent of Talbot’s composition for Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland©. The chilly noises of prison life (such as the reverberations of metal doors being unlocked and slammed) that opened Act II hammered the harsh reality home. Wilde’s time of self-indulgence was over. The same applied to Dorian Gray. The moment Gray cut up his portrait, the music suddenly went into a spin as if he (and Wilde) had a mental blackout. Tinnitus-like squeaks and creeks and confusing noise attested to Wilde’s cognitive overload.

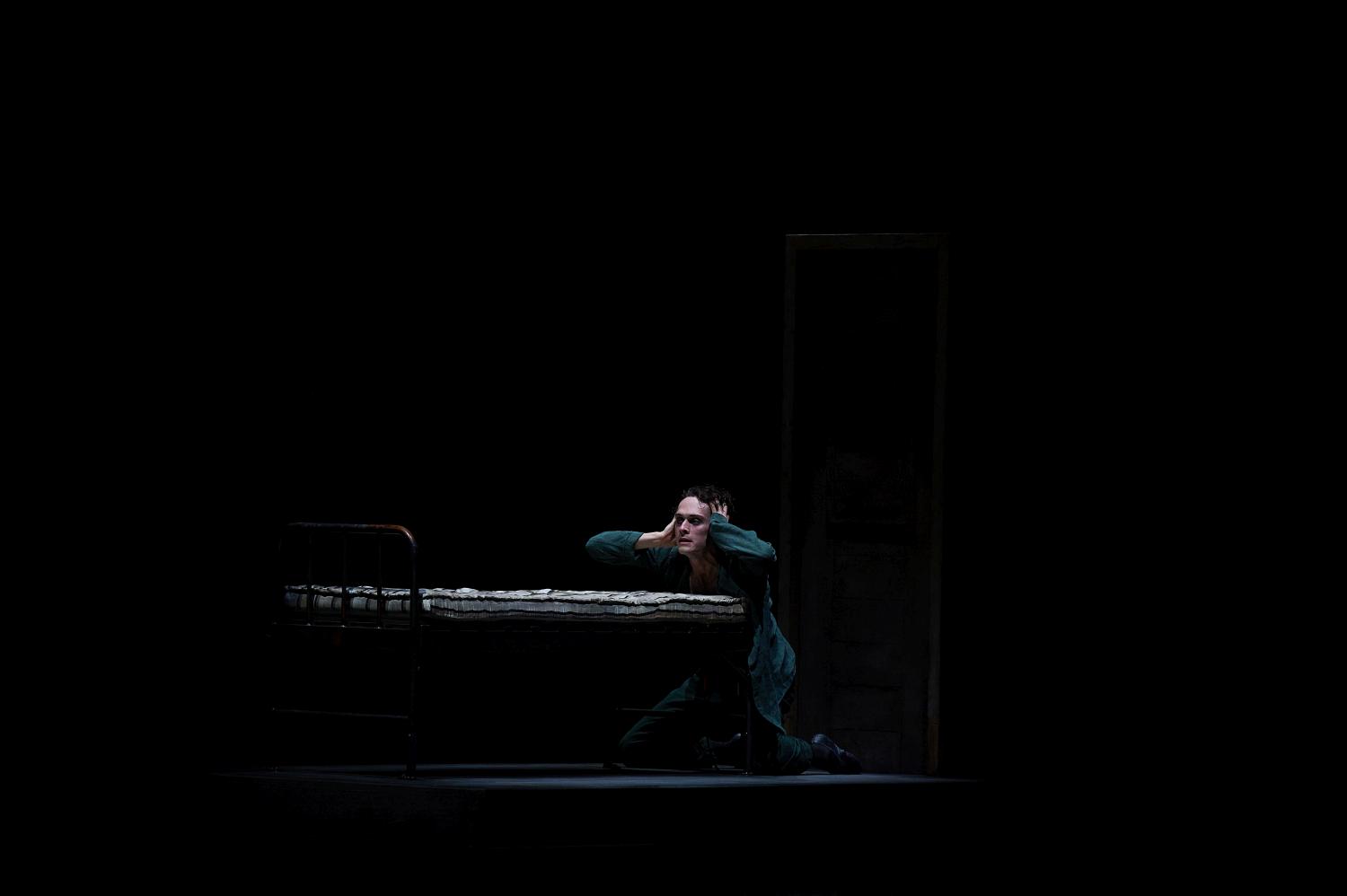

Jean-Marc Puissant’s stage design switched smoothly between a stifling court, a sedate salon, the Wildes’ neat home, and a shady queer bar. A metal door and a tubular steel frame bed with an uncomfortably flimsy mattress represented Wilde’s cell. Though its walls were invisible, Wilde’s restricted range of movements defined the narrow space. The blossoming trees that symbolized the biotope of the nightingale seemed related to the tree in the Bohemian countryside of Wheeldon’s The Winter’s Tale when cleared of its tree decoration.

Jean-Marc Puissant’s stage design switched smoothly between a stifling court, a sedate salon, the Wildes’ neat home, and a shady queer bar. A metal door and a tubular steel frame bed with an uncomfortably flimsy mattress represented Wilde’s cell. Though its walls were invisible, Wilde’s restricted range of movements defined the narrow space. The blossoming trees that symbolized the biotope of the nightingale seemed related to the tree in the Bohemian countryside of Wheeldon’s The Winter’s Tale when cleared of its tree decoration.

Wheeldon exploited a full choreographic toolbox to characterize Victorian society and the main protagonists. His highly sensual language might have been divisive, but that was what he was after.

Wilde (Callum Linnane) didn’t bother with the limits of social norms (at one point symbolized by unwieldy, wooden benches that the court ushers used to bar the way of dissenters). His family life seemed all sunshine and sparkles, but the effeminate artificiality he displayed at times didn’t fit with his role as a dad, and his effusive public adoration for actresses made him a lousy husband. Wilde felt special, loved to be at the center of admiration, and flaunted himself as a genius blessed with an exhausting amount of prowess. Not a single thought was wasted on his family when he allowed his homosexuality to run free. Only in prison did he begin to reflect on himself. His wife, Constance (Sharni Spencer), seemed tame but suspected (or knew) more than she preferred and bore it without flinching.

Wilde (Callum Linnane) didn’t bother with the limits of social norms (at one point symbolized by unwieldy, wooden benches that the court ushers used to bar the way of dissenters). His family life seemed all sunshine and sparkles, but the effeminate artificiality he displayed at times didn’t fit with his role as a dad, and his effusive public adoration for actresses made him a lousy husband. Wilde felt special, loved to be at the center of admiration, and flaunted himself as a genius blessed with an exhausting amount of prowess. Not a single thought was wasted on his family when he allowed his homosexuality to run free. Only in prison did he begin to reflect on himself. His wife, Constance (Sharni Spencer), seemed tame but suspected (or knew) more than she preferred and bore it without flinching.

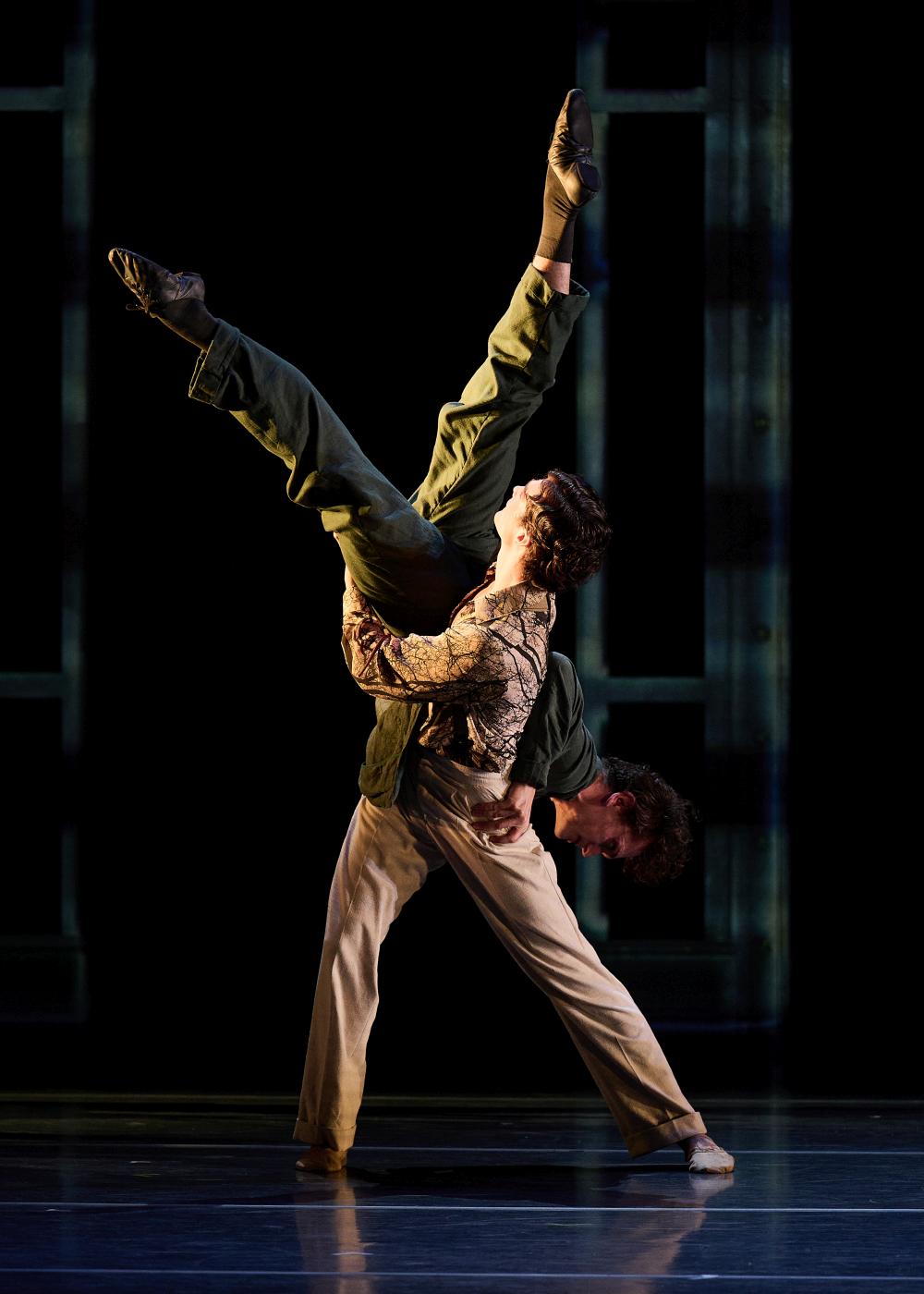

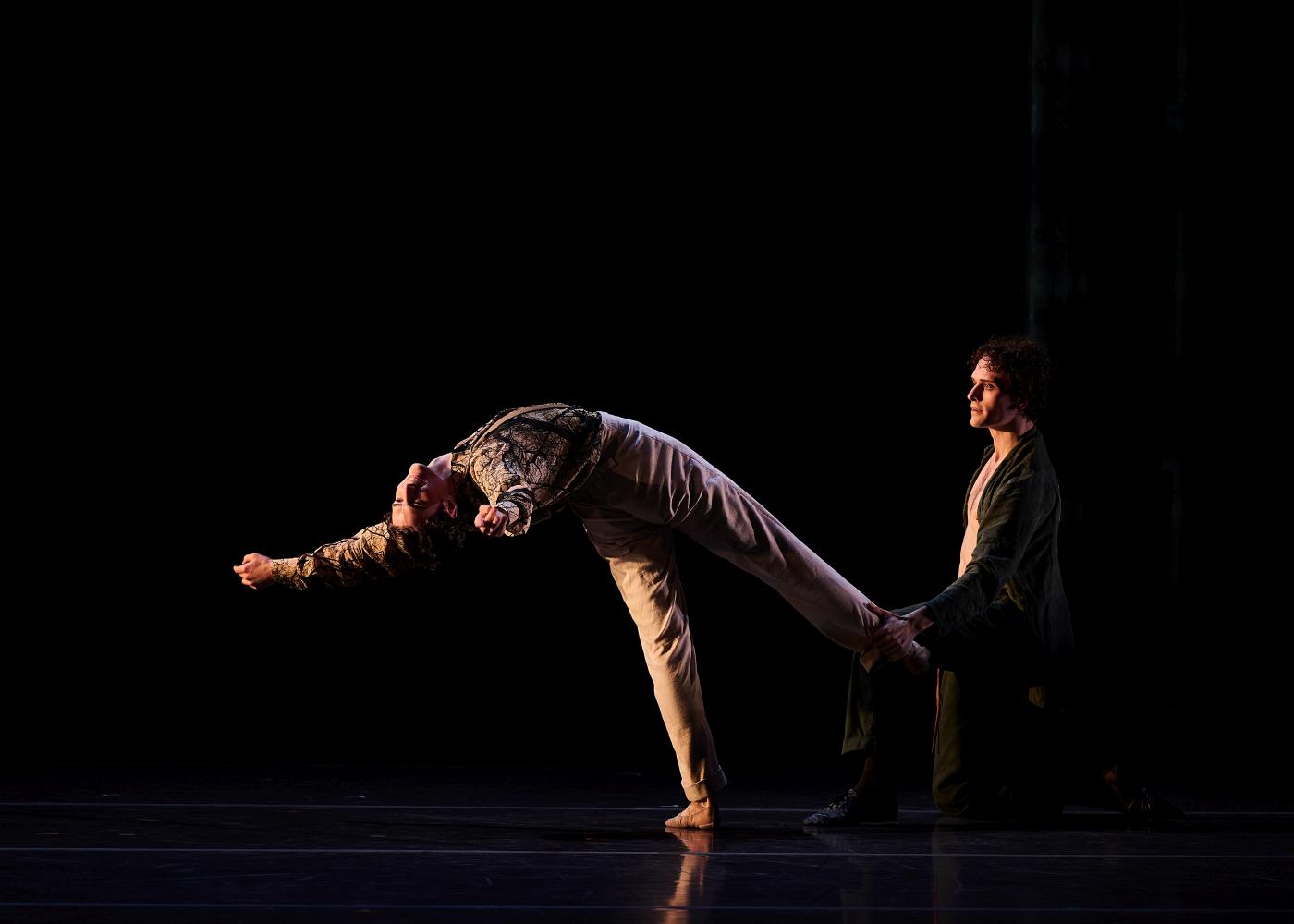

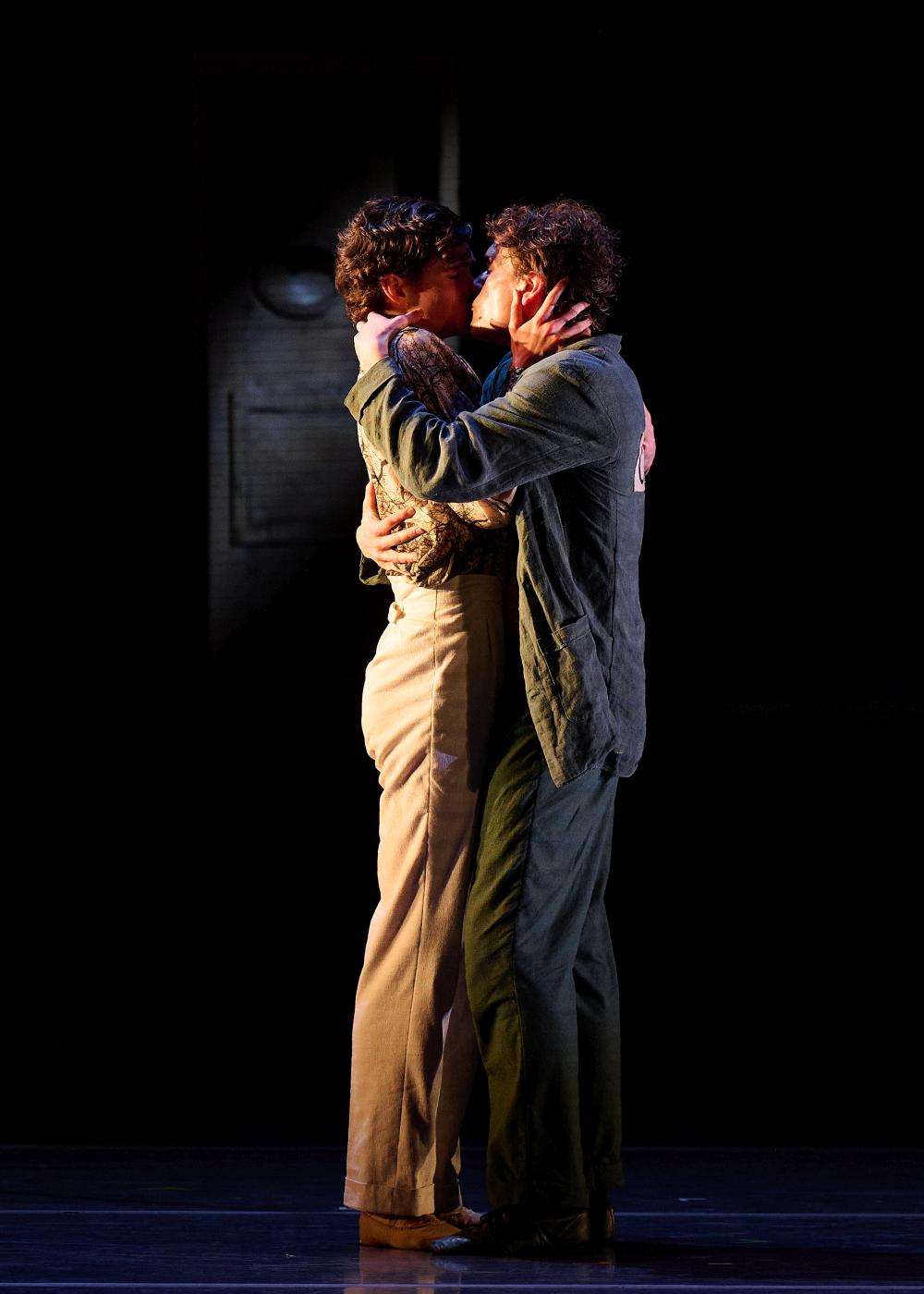

As Robbie Ross, every pore of Joseph Caley’s body oozed seduction. Magnetically attractive, each gesture and step was an indecent invitation or demand, which Wilde seemed obliged to answer. Benjamin Garrett’s Lord Alfred Douglas/Bosie was a handsome, spoiled lad whose sensual passions turned nasty when he didn’t get what he wanted. The moment his father, Lord Queensberry (Steven Heathcote), signaled his intent to crack down on him, he immediately toed the line.

One of the three actresses who Wilde unabashedly idolized was Sarah Bernhardt (Benedicte Bemet). He watched her play the title role of Jean Racine’s Phèdre. Her petite body seemed overtaken by drama as her arms shot out and her trembling hands reached for salvation. The second actress, Lillie Langtry (Mia Heathcote), played Cleopatra in Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra. Her eyes narcissistically fixed on her image in the hand mirror; she fell from her divan, climbed to her feet, and stepped awkwardly back and forth (it would be interesting to know to what extent her solo matched Langtry’s original performance in 1891). Ellen Terry (Jill Ogai), a longstanding romantic partner of Shakespeare, thrilled Wilde with her performance of the unhinged Ophelia. She flung herself in a series of turns with her upper body bent forward as if trying to swim toward a safer shore. The sternly looking critic who watched all three performances might have been the young George Bernard Shaw.

One of the three actresses who Wilde unabashedly idolized was Sarah Bernhardt (Benedicte Bemet). He watched her play the title role of Jean Racine’s Phèdre. Her petite body seemed overtaken by drama as her arms shot out and her trembling hands reached for salvation. The second actress, Lillie Langtry (Mia Heathcote), played Cleopatra in Shakespeare’s Anthony and Cleopatra. Her eyes narcissistically fixed on her image in the hand mirror; she fell from her divan, climbed to her feet, and stepped awkwardly back and forth (it would be interesting to know to what extent her solo matched Langtry’s original performance in 1891). Ellen Terry (Jill Ogai), a longstanding romantic partner of Shakespeare, thrilled Wilde with her performance of the unhinged Ophelia. She flung herself in a series of turns with her upper body bent forward as if trying to swim toward a safer shore. The sternly looking critic who watched all three performances might have been the young George Bernard Shaw.

Ako Kondo’s Nightingale was the ballet’s only spiritual figure. Her jerky, bird-like movements, a gorgeous headdress in the form of a nightingale’s head (also by Puissant), and—above all—her compassion made her appear vulnerable, but nothing could harm the principle of love she represented. (Although, overall erotic vibes also pervaded her self-sacrificial death.) The student for whom she searched for the red rose was played by Benjamin Garrett. His love interest (Katherine Sonnekus) was more interested in material than inner values though.

Adam Elmes danced the role of the egomaniacal Dorian Gray whose portrait was painted by Viktor Estévez’s Basil Hallward. Elmes also played Wilde’s shadow. Bryce Latham and Henry Berlin portrayed Wilde’s two sons, Cyril and Vyvyan, and Lucien Xu and Elijah Trevitt were the salacious cross-dressers who entertained and teased the queer guests at the bar. Their eagerness to put themselves in the limelight reminded me of the ugly sisters in Ashton’s Cinderella.

| Links: | Website of the Australian Ballet | |

| David Hallberg on Christopher Wheeldon’s Oscar© | ||

| Inside Oscar©: Meet the Characters | ||

| Dancers on becoming Oscar Wilde | ||

| Choreographing Oscar© with Christopher Wheeldon | ||

| Unpacking the creative process of Oscar© with Christopher Wheeldon | ||

| Designing Oscar© with Jean-Marc Puissant | ||

| Composing Oscar© with Joby Talbot | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), Sharni Spencer (Constance Wilde), and Joseph Caley (Robbie Ross), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 |

| 2. | Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 | |

| 3. | Mia Heathcote (Lillie Langtry), Benedicte Bemet (Sarah Bernhardt), and Jill Ogai (Ellen Terry), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 | |

| 4. | Ako Kondo (Nightingale), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 | |

| 5. | Ensemble, “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 | |

| 6. | Ensemble, “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 | |

| 7. | Benjamin Garrett (Lord Alfred Douglas/Bosie) and Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 | |

| 8. | Benjamin Garrett (Lord Alfred Douglas/Bosie) and Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 |

|

| 9. | Benjamin Garrett (Lord Alfred Douglas/Bosie) and Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 |

|

| 10. | Benjamin Garrett (Lord Alfred Douglas/Bosie) and Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 |

|

| 11. | Benjamin Garrett (Lord Alfred Douglas/Bosie) and Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 |

|

| 12. | Benjamin Garrett (Lord Alfred Douglas/Bosie) and Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 |

|

| 13. | Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 |

|

| 14. | Callum Linnane (Oscar Wilde) and Ako Kondo (Nightingale), “Oscar©” by Christopher Wheeldon, The Australian Ballet 2024 | |

| all photos © Christopher Rodgers-Wilson | ||

| Editing: | Kayla Kauffman |