“Stravinsky. Puppets. Dances”

Ballet of the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Music Theatre

Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Music Theatre

Moscow, Russia

April 20, 2025

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2025 by Ilona Landgraf

The Stanislavsky Ballet’s new double bill, Stravinsky. Puppets. Dances, attracted large crowds, especially because they scheduled only five performances over three consecutive days. The two ballets, Petrushka and The Firebird, were originally choreographed by Michel Fokine for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1911 and 1910, respectively. Both are set to compositions by Igor Stravinsky. The Stanislavsky Theatre presented new interpretations by Kirill Radev (The Firebird)—a former choreographer of the Barcelona Ballet—and Konstantin Semenov (Petrushka)—a dancer-cum-choreographer from the company’s own ranks, whose one-act piece, Through the Looking-Glass I saw in 2023. Both teamed up with stage director Alexey Frandetti (a Tashkent native who later moved to Moscow) and set designer Viktor Nikonenko. The internationally awarded Nikonenko is a puppet maker at Moscow’s State Academic Central Puppet Theater S.V. Obraztsov, which cooperated with the Stanislavsky Theatre for the first time (an exhibition of puppets and photos from the S.V. Obraztsov museum was shown at the Stanislavsky as well).

The Stanislavsky Ballet’s new double bill, Stravinsky. Puppets. Dances, attracted large crowds, especially because they scheduled only five performances over three consecutive days. The two ballets, Petrushka and The Firebird, were originally choreographed by Michel Fokine for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes in 1911 and 1910, respectively. Both are set to compositions by Igor Stravinsky. The Stanislavsky Theatre presented new interpretations by Kirill Radev (The Firebird)—a former choreographer of the Barcelona Ballet—and Konstantin Semenov (Petrushka)—a dancer-cum-choreographer from the company’s own ranks, whose one-act piece, Through the Looking-Glass I saw in 2023. Both teamed up with stage director Alexey Frandetti (a Tashkent native who later moved to Moscow) and set designer Viktor Nikonenko. The internationally awarded Nikonenko is a puppet maker at Moscow’s State Academic Central Puppet Theater S.V. Obraztsov, which cooperated with the Stanislavsky Theatre for the first time (an exhibition of puppets and photos from the S.V. Obraztsov museum was shown at the Stanislavsky as well).

Ekaterina Gutkovskaya and Anastasia Pugashkina designed the costumes; Ivan Vinogradov ran the lighting; Ilya Starilov contributed videos. Stravinsky. Puppets. Dances was part of the open art festival, Chereshnevy Les, which features various theater performances, concerts, and art exhibitions.

Ekaterina Gutkovskaya and Anastasia Pugashkina designed the costumes; Ivan Vinogradov ran the lighting; Ilya Starilov contributed videos. Stravinsky. Puppets. Dances was part of the open art festival, Chereshnevy Les, which features various theater performances, concerts, and art exhibitions.

For Petrushka, Semenov for the most part kept Alexandre Benois’s original libretto but dropped the reference to a fair. Instead, he zoomed in on a puppet theater stage, upon which the loves and jealousies of the ballet’s three puppet protagonists—Petrushka (Evgeny Zhukov), the Ballerina (Oxana Kardash), and the Moor (Denis Dmitriev)—play out. A black-and-white video showed their puppeteer walking through a backstage corridor. His face wasn’t discernible, and, later, we only saw his hands on a backdrop video manipulating the puppets. The moment the curtain rose, the video’s puppets turned into huge, real ones. Their living souls (and, simultaneously, their puppeteers) were dancers who rolled them around and moved their arms. Once they stepped from behind their puppet shells,

For Petrushka, Semenov for the most part kept Alexandre Benois’s original libretto but dropped the reference to a fair. Instead, he zoomed in on a puppet theater stage, upon which the loves and jealousies of the ballet’s three puppet protagonists—Petrushka (Evgeny Zhukov), the Ballerina (Oxana Kardash), and the Moor (Denis Dmitriev)—play out. A black-and-white video showed their puppeteer walking through a backstage corridor. His face wasn’t discernible, and, later, we only saw his hands on a backdrop video manipulating the puppets. The moment the curtain rose, the video’s puppets turned into huge, real ones. Their living souls (and, simultaneously, their puppeteers) were dancers who rolled them around and moved their arms. Once they stepped from behind their puppet shells,  the puppeteers jumped and swirled vigorously across the stage. Stravinsky’s throbbing percussion beat the rhythm of the flutter of their wide, black skirts. They lunged onto the floor, spiraled in the air, and swirled their arms dynamically. At times, their movements and facial expressions resembled those of puppets.

the puppeteers jumped and swirled vigorously across the stage. Stravinsky’s throbbing percussion beat the rhythm of the flutter of their wide, black skirts. They lunged onto the floor, spiraled in the air, and swirled their arms dynamically. At times, their movements and facial expressions resembled those of puppets.

The puppet shells surrounded the protagonist like a silent audience, closed in on the desperate Petrushka like a wall, or chased their puppeteers off stage. They turned their heads to look sideways and, depending on the atmosphere, changed the colors of their caps, floor-length robes, and faces. Similarly designed puppets were lowered several times on strings from the fly loft into the air. Other puppets joined them: a huge, rollable bear sewed from various pink-patterned fabrics; a horse head made of the same fabric that was mounted on the handlebar of a tricycle (its long, red reins served as skipping ropes for the puppeteers); two short puppet drummers; a barrel organ on four legs (whose pert feet substituted for the lack of sight); and a flying, golden-faced demon with a fiery-red, gauzy tail.

Zhukov’s Petrushka was a hapless softie whose nature was as unblemished as his white outfit. His heart was generous but lacked the strength to realize its desires. As much as he clenched his fist toward his master, he remained feeble. His arms continued to swing in overlong sleeves as if boneless, his backbone seemed made of rubber, and his woolen cap resembled a bedcap. It was no wonder that Kardash’s Ballerina fled his advances. Very blonde and wearing a voluptuous, bright pink petticoat, she looked (and strutted) like Barbie incarnate. Her affection was lavished on the Moor, a narcissistic Ken doll in golden armor and with a golden head of hair. Apart from admiring himself in the mirror, posing like a bodybuilder, patting his steely muscles, and kissing his biceps, he was potent enough to dominate the terrain.

Zhukov’s Petrushka was a hapless softie whose nature was as unblemished as his white outfit. His heart was generous but lacked the strength to realize its desires. As much as he clenched his fist toward his master, he remained feeble. His arms continued to swing in overlong sleeves as if boneless, his backbone seemed made of rubber, and his woolen cap resembled a bedcap. It was no wonder that Kardash’s Ballerina fled his advances. Very blonde and wearing a voluptuous, bright pink petticoat, she looked (and strutted) like Barbie incarnate. Her affection was lavished on the Moor, a narcissistic Ken doll in golden armor and with a golden head of hair. Apart from admiring himself in the mirror, posing like a bodybuilder, patting his steely muscles, and kissing his biceps, he was potent enough to dominate the terrain.

Unlike Petrushka, the Ballerina and the Moor had life-size puppet doubles, each moved by three puppeteers. The face of the Moor’s puppet seemed modeled after Sergei Obraztsov’s (1901-1992), the namesake of the Obraztsov Puppet Theater who established puppet theater as an art form in the Soviet Union. At times, the puppet doubles replaced Kardash and Dmitriev, dancing together or flying across the stage like figureheads of a ship’s bow.

Unlike Petrushka, the Ballerina and the Moor had life-size puppet doubles, each moved by three puppeteers. The face of the Moor’s puppet seemed modeled after Sergei Obraztsov’s (1901-1992), the namesake of the Obraztsov Puppet Theater who established puppet theater as an art form in the Soviet Union. At times, the puppet doubles replaced Kardash and Dmitriev, dancing together or flying across the stage like figureheads of a ship’s bow.

Only once, when the Moor was distracted by self-adulation, did Petrushka have the chance to flirt with the Ballerina and her puppet double. But the second the Moor noticed them, he confronted Petrushka like a boxer in a ring. He rained down punches and kicks upon Petrushka. Both twirled the Ballerina like a wheel of fortune. Petrushka even boxed the Moor’s ears, but—alas! One breath later, he crawled out of the combat zone on all fours. His defeat was thorough. As he pulled out the red ribbon that symbolized his

Only once, when the Moor was distracted by self-adulation, did Petrushka have the chance to flirt with the Ballerina and her puppet double. But the second the Moor noticed them, he confronted Petrushka like a boxer in a ring. He rained down punches and kicks upon Petrushka. Both twirled the Ballerina like a wheel of fortune. Petrushka even boxed the Moor’s ears, but—alas! One breath later, he crawled out of the combat zone on all fours. His defeat was thorough. As he pulled out the red ribbon that symbolized his  heart and handed it to the Ballerina and the Moor, he lost his lifeblood. Upon the puppet master’s hands gesturing “Finito!” in the backdrop video, the onstage puppeteers disassembled Petrushka and piled his body parts into a heap.

heart and handed it to the Ballerina and the Moor, he lost his lifeblood. Upon the puppet master’s hands gesturing “Finito!” in the backdrop video, the onstage puppeteers disassembled Petrushka and piled his body parts into a heap.

His spirit returned in a video after the curtain had gone down. The video rotated images of the faces of different performers of Petrushka, whose expressions wavered between seriousness and a smile. There was nothing to pity, being Petrushka was just fate.

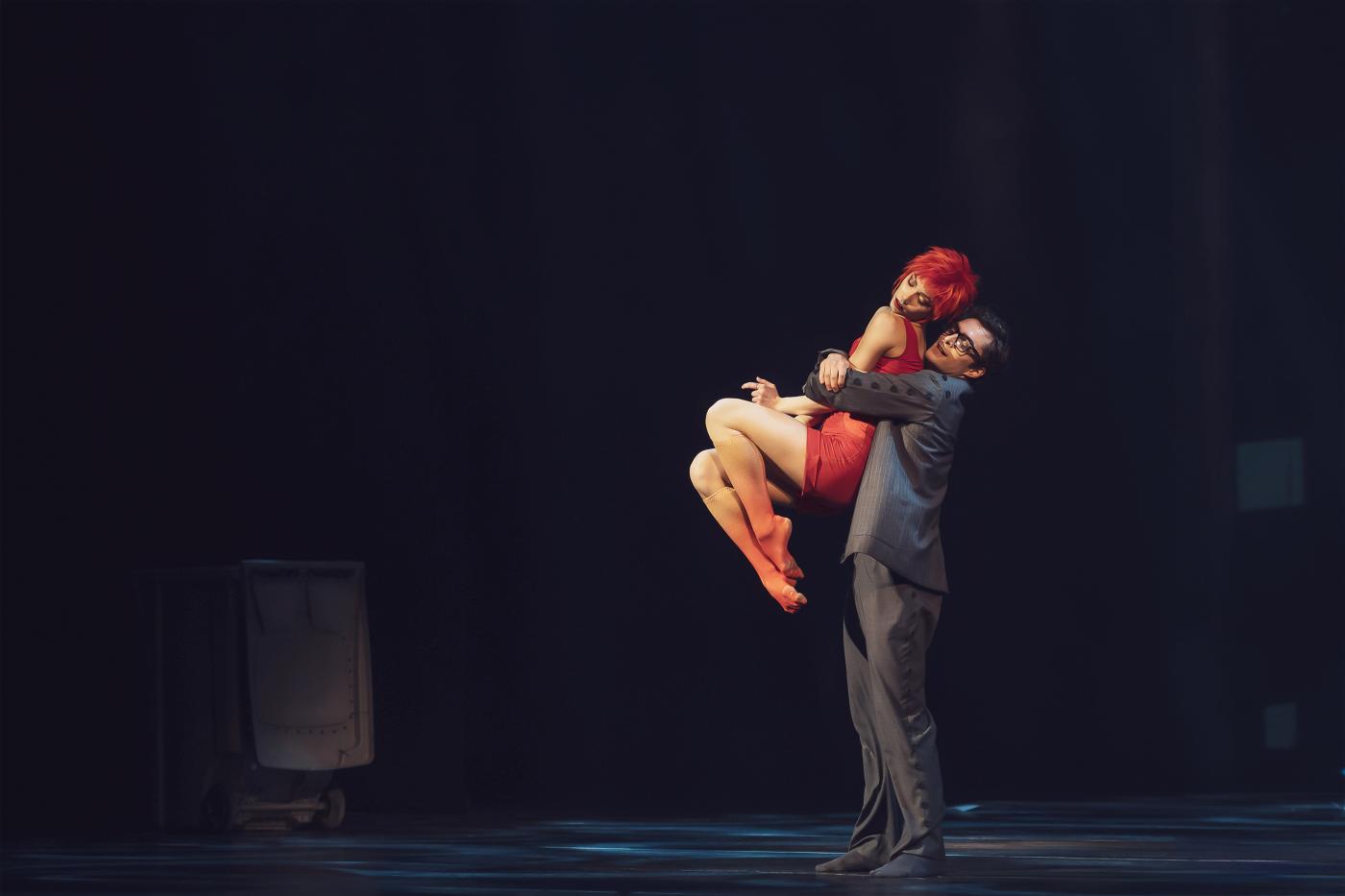

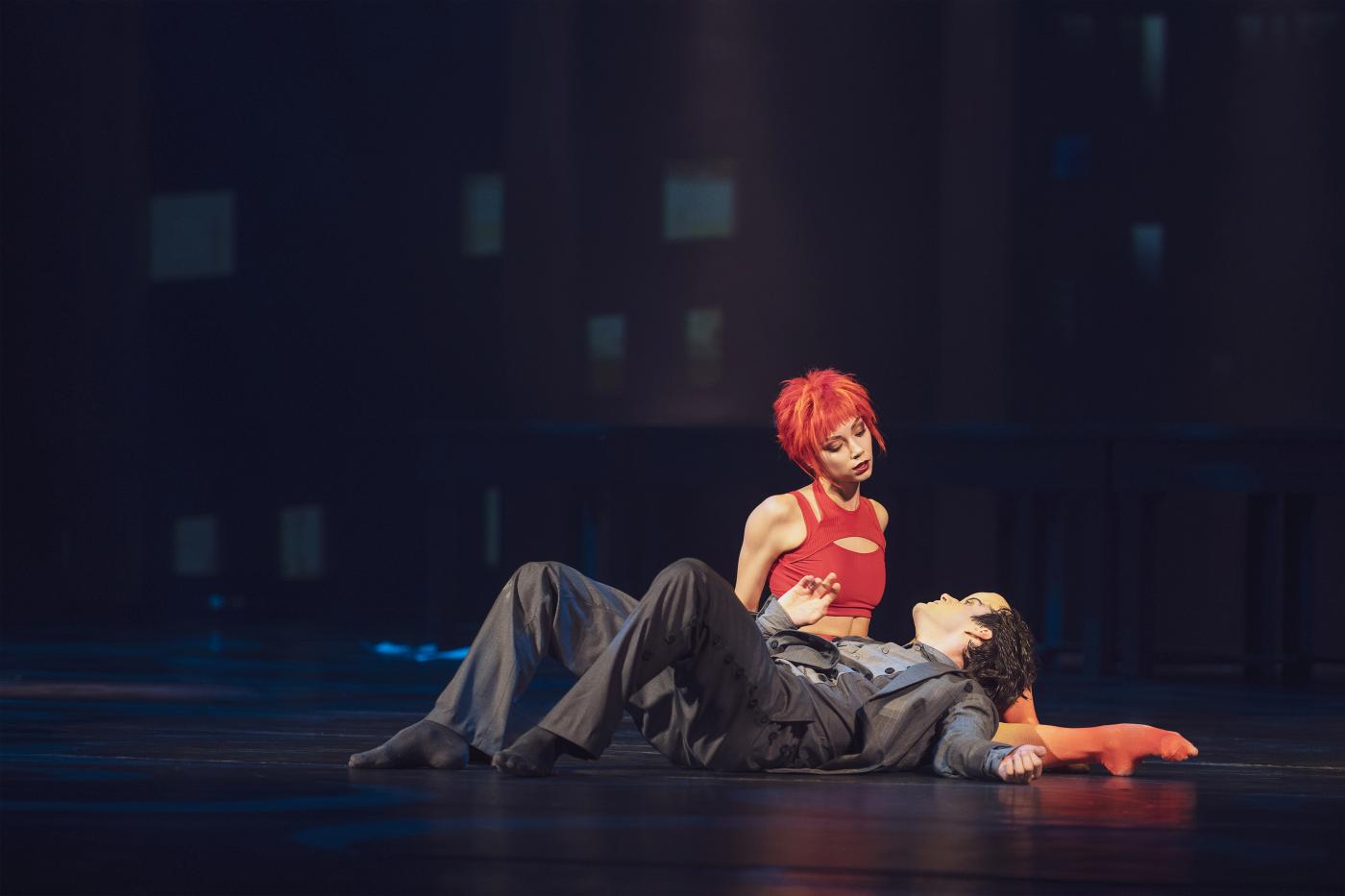

Unlike Petrushka’s, Frandetti’s libretto for The Firebird has little in common with the original. Its Ivan (Artur Mkrtchyan) isn’t a prince but rather an employee in a construction company’s all-glass penthouse office. (Perhaps the penthouse hinted at the palace “all of glass” in Yakov Polonsky’s 1844 poem, A Winter’s Journey, which is said to have inspired the original ballet?) A bespectacled guy in sneakers, brooding over his laptop, Ivan worked overtime. But he  racked his brain in vain. Presumably, he was still challenged by work projects projected from his laptop onto the curtain near the end of the break: construction sketches of the BRUSOV house, an iconic Moscow residence constructed by VOS’HOD, an official partner of the Stanislavsky Theatre for two years. But whatever the task, Ivan’s mind was as gray as his outfit and the office. The latter had just been cleaned by diligent cleaning staff in gray overalls. In the meantime, Ivan’s desperation deepened. But suddenly, a spark of inspiration in the form of red light flew by like a firefly, immediately attracting his attention. It played cat-and-mouse with him until he discovered that it was just a red-lit dust mop. As he contemptuously threw it away, the mop morphed into a gleaming firebird. Helped by its puppeteers, it rested briefly on Ivan’s hand, but he could neither catch it nor get hold of a single feather. The bird flew off, but upon searching (and as if to prove that trash can be turned into treasure), Ivan found it in the trash can left behind by the cleaners. The firebird he pulled out had adopted a human nature (that of Elena Solomyanko), had a fiery red mop of hair, and was wearing pants, socks, and a top in the same color. Wavering between trust and shyness, the bird stayed elusive and wayward. It even made Ivan hide under the office’s long working table. Only after some back and forth did the firebird crawl over to Ivan and rest its head in his lap.

racked his brain in vain. Presumably, he was still challenged by work projects projected from his laptop onto the curtain near the end of the break: construction sketches of the BRUSOV house, an iconic Moscow residence constructed by VOS’HOD, an official partner of the Stanislavsky Theatre for two years. But whatever the task, Ivan’s mind was as gray as his outfit and the office. The latter had just been cleaned by diligent cleaning staff in gray overalls. In the meantime, Ivan’s desperation deepened. But suddenly, a spark of inspiration in the form of red light flew by like a firefly, immediately attracting his attention. It played cat-and-mouse with him until he discovered that it was just a red-lit dust mop. As he contemptuously threw it away, the mop morphed into a gleaming firebird. Helped by its puppeteers, it rested briefly on Ivan’s hand, but he could neither catch it nor get hold of a single feather. The bird flew off, but upon searching (and as if to prove that trash can be turned into treasure), Ivan found it in the trash can left behind by the cleaners. The firebird he pulled out had adopted a human nature (that of Elena Solomyanko), had a fiery red mop of hair, and was wearing pants, socks, and a top in the same color. Wavering between trust and shyness, the bird stayed elusive and wayward. It even made Ivan hide under the office’s long working table. Only after some back and forth did the firebird crawl over to Ivan and rest its head in his lap.

The eight female workmates who simultaneously arrived at the office shortly afterward might have been inspired by the virgins in the original libretto who are held captive by the evil sorcerer Koschei. All wore floor-length, stiff, gray skirts and gray headscarves, hid behind dark sunglasses, and carried a laptop under their arm. Toward Ivan, they behaved like harpies toward an underling. One woman condescendingly handed him the sneakers that he had doffed when meeting the firebird. Given the female superiority, Ivan squirmed like a worm. Yet the women’s in-sync showmanship was superficial and dragged on. After slipping out of their skirts (revealing gray pant suits beneath), they knelt in line at the front stage and, for whatever reason, squiggled their silver pumps with their hands as if to imitate the snakes of a snake charmer.

The eight female workmates who simultaneously arrived at the office shortly afterward might have been inspired by the virgins in the original libretto who are held captive by the evil sorcerer Koschei. All wore floor-length, stiff, gray skirts and gray headscarves, hid behind dark sunglasses, and carried a laptop under their arm. Toward Ivan, they behaved like harpies toward an underling. One woman condescendingly handed him the sneakers that he had doffed when meeting the firebird. Given the female superiority, Ivan squirmed like a worm. Yet the women’s in-sync showmanship was superficial and dragged on. After slipping out of their skirts (revealing gray pant suits beneath), they knelt in line at the front stage and, for whatever reason, squiggled their silver pumps with their hands as if to imitate the snakes of a snake charmer.

The next time the firebird appeared, it induced dystopian visions in Ivan that turned the office into a witch’s cauldron. Wafts of mist mingled with flashes of strobe lights, gray men overpowered Ivan and, accompanied by thundering percussion, a huge kraken (presumably a modern version of Koschei) lowered itself onto the worktable. Its head’s blinking lights looked like warning lights at a construction site, and its grabby, flexible arms were assembled from plastic pipes. The chaos intensified when some dubious gray men crawled out of the trap door (i.e., the underground). Ivan had already dodged behind a concrete pillar when Solomyanko’s firebird wriggled herself like a sexy icon on the worktable. Red glinting sparks revolved around her. As suddenly as the nightmare had begun, calm set in. The flames that ate the skyline outside were silent. Despite the inferno, Ivan shouldered the firebird and made it fly. Still, it wasn’t clear if the magic

The next time the firebird appeared, it induced dystopian visions in Ivan that turned the office into a witch’s cauldron. Wafts of mist mingled with flashes of strobe lights, gray men overpowered Ivan and, accompanied by thundering percussion, a huge kraken (presumably a modern version of Koschei) lowered itself onto the worktable. Its head’s blinking lights looked like warning lights at a construction site, and its grabby, flexible arms were assembled from plastic pipes. The chaos intensified when some dubious gray men crawled out of the trap door (i.e., the underground). Ivan had already dodged behind a concrete pillar when Solomyanko’s firebird wriggled herself like a sexy icon on the worktable. Red glinting sparks revolved around her. As suddenly as the nightmare had begun, calm set in. The flames that ate the skyline outside were silent. Despite the inferno, Ivan shouldered the firebird and made it fly. Still, it wasn’t clear if the magic  creature supported or harmed him. The answer to this question was made clear when Solomyanko kissed him and continued to kiss him until he suffocated. Framed by licking flames, she strolled off stage in satisfaction.

creature supported or harmed him. The answer to this question was made clear when Solomyanko kissed him and continued to kiss him until he suffocated. Framed by licking flames, she strolled off stage in satisfaction.

Parts of the ballet had felt lengthy and labored until then. But matters took a surprising twist when the Firebird and Prince Igor from Diaghilev’s time appeared (Anfisa Oschepkova portrayed Tamara Karsavina; Evgeny Dubrovsky danced the role of Michel Fokine). The energy sprang back to life like a spring fountain. Maybe gray and dreary times are essential to prepare the phoenix for its next rise from the ashes.

Conductor Roman Kaloshin and the Orchestra of the Stanislavsky Theatre proved that Stravinsky’s music has consistent punch.

| Links: | Website of the Stanislavsky and Nemirovich-Danchenko Moscow Music Theatre | |

| “Stravinsky. Puppets. Dances” (video) | ||

| “Stravinsky. Puppets. Dances”- The Puppets | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Denis Dmitriev (Moor), Evgeny Zhukov (Petrushka), and Oxana Kardash (Ballerina); “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

| 2. | Denis Dmitriev (Moor), “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 | |

| 3. | Evgeny Zhukov (Petrushka) and ensemble, “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 | |

| 4. | Oxana Kardash (Ballerina), Moor, and ensemble; “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 5. | Denis Dmitriev (Moor), Ballerina, and ensemble; “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 | |

| 6. | Dmitry Kazimirov and Maxim Skorlygin (Barrel Organ), “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 7. | Denis Dmitriev (Moor), “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 8. | Denis Dmitriev (Moor), Oxana Kardash (Ballerina), and Evgeny Zhukov (Petrushka); “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 | |

| 9. | Evgeny Zhukov (Petrushka) and Ballerina; “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 10. | Evgeny Zhukov (Petrushka), and Oxana Kardash (Ballerina); “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 11. | Evgeny Zhukov (Petrushka), “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 12. | Evgeny Zhukov (Petrushka), Oxana Kardash (Ballerina), Denis Dmitriev (Moor), and ensemble; “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 | |

| 13. | Ensemble, “Petrushka” by Konstantin Semenov, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 | |

| 14. | Artur Mkrtchyan (Ivan), Firebird, and ensemble; “The Firebird” by Kirill Radev, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 15. | Elena Solomyanko (Firebird) and Artur Mkrtchyan (Ivan), “The Firebird” by Kirill Radev, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 16. | Elena Solomyanko (Firebird) and Artur Mkrtchyan (Ivan), “The Firebird” by Kirill Radev, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 17. | Elena Solomyanko (Firebird) and Artur Mkrtchyan (Ivan), “The Firebird” by Kirill Radev, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 18. | Elena Solomyanko (Firebird) and Artur Mkrtchyan (Ivan), “The Firebird” by Kirill Radev, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 |

|

| 19. | Artur Mkrtchyan (Ivan) and Elena Solomyanko (Firebird), “The Firebird” by Kirill Radev, Stanislavsky Ballet 2025 | |

| all photos © Stanislavsky Ballet/Yulia Gubina | ||

| Editing: | Kayla Kauffman |