Brimful

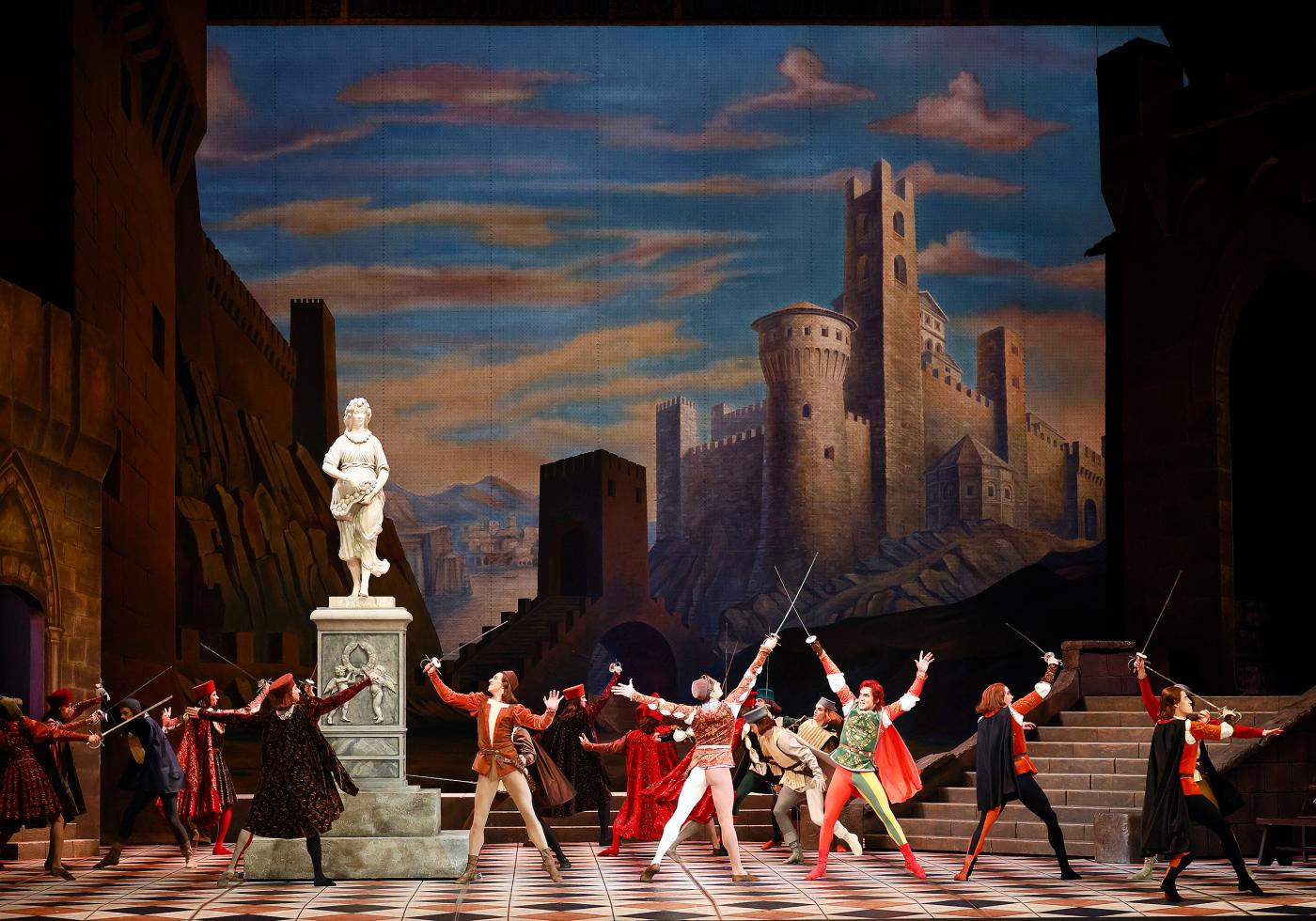

“Cipollino”

Bolshoi Ballet

Bolshoi Theatre (New Stage)

Moscow, Russia

March 08, 2025 (matinee and evening performance)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2025 by Ilona Landgraf

The boy Cippolino (Little Onion), the hero of Gianni Rodari’s 1957 children’s book Adventures of Cipollino, enjoyed an international career. He was especially popular in eastern countries and a famous cartoon and film figure in the Soviet Union. A ballet adaption by Genrikh Mayorov (1936-2022) entered the Bolshoi Ballet’s repertory three years after its Kiev premiere. Cipollino was revived at the Bolshoi earlier this season and still attracts crowds. Though a children’s fairy tale, adults can appreciate the production, especially when danced at top quality. I saw a matinee attended primarily by children and their parents as well as a sold-out evening performance.

The boy Cippolino (Little Onion), the hero of Gianni Rodari’s 1957 children’s book Adventures of Cipollino, enjoyed an international career. He was especially popular in eastern countries and a famous cartoon and film figure in the Soviet Union. A ballet adaption by Genrikh Mayorov (1936-2022) entered the Bolshoi Ballet’s repertory three years after its Kiev premiere. Cipollino was revived at the Bolshoi earlier this season and still attracts crowds. Though a children’s fairy tale, adults can appreciate the production, especially when danced at top quality. I saw a matinee attended primarily by children and their parents as well as a sold-out evening performance.

The young Cipollino and his family are members of jovial townsfolk who are anthropomorphic fruits and vegetables—Cobbler Grape, Professor Pear, Godfather Pumpkin, and the Radish family, whose daughter, Little Radish, becomes Cipollino’s best buddy. They’re ruled by the high-handed, eccentric Prince Lemon whose court includes an acerbic guard, ludicrous knights, and the two overexcited Countesses Cherry. (more…)