A Farewell Triplet

“Pathétique” (“Divertimento No. 15”/“Summerspace”/“Pathétique”)

Vienna State Ballet

Vienna State Opera

Vienna, Austria

April 09, 2025 (live stream)

by Ilona Landgraf

Copyright © 2025 by Ilona Landgraf

Triple bills have become a trademark of the Vienna State Ballet since Martin Schläpfer took over as artistic director in 2020. The latest, Pathétique, is titled after Schläpfer’s newest and last creation. As on previous occasions, the program’s safe and well-tested base was a Balanchine followed by Cunningham’s Summerspace.

Triple bills have become a trademark of the Vienna State Ballet since Martin Schläpfer took over as artistic director in 2020. The latest, Pathétique, is titled after Schläpfer’s newest and last creation. As on previous occasions, the program’s safe and well-tested base was a Balanchine followed by Cunningham’s Summerspace.

A sense of nostalgia pervaded the premiere evening the title of which summarized the disposition Schläpfer will be remembered for. His five-year tenure, which will terminate this autumn, failed to propel the company toward artistic heights. Whether his successor, Alessandra Ferri, will achieve more, is written in the stars. Ferri purchased pieces by Alexei Ratmansky, Justin Peck, Thierry Malandain, Twyla Tharp, Pam Tanowitz, Lar Lubovitch, and others for the next season; Schläpfer’s choreographies will be stowed away in the archive. New creations aren’t scheduled.

A sense of nostalgia pervaded the premiere evening the title of which summarized the disposition Schläpfer will be remembered for. His five-year tenure, which will terminate this autumn, failed to propel the company toward artistic heights. Whether his successor, Alessandra Ferri, will achieve more, is written in the stars. Ferri purchased pieces by Alexei Ratmansky, Justin Peck, Thierry Malandain, Twyla Tharp, Pam Tanowitz, Lar Lubovitch, and others for the next season; Schläpfer’s choreographies will be stowed away in the archive. New creations aren’t scheduled.

But I return to the premiere of Pathétique, which was streamed live and attended by an in-house audience faithful to Schläpfer.

But I return to the premiere of Pathétique, which was streamed live and attended by an in-house audience faithful to Schläpfer.

Divertimento No.15 (1956), set to a revised version of Mozart’s eponymous composition, is one of Balanchine’s ageless pieces. Perhaps due to the fraught and messy times we’re in, watching eight principals (five women and three men) and a female corps of eight perform with courtly elegance has a soothing effect on the mind. Their white, light blue, and yellow-colored tutus, pants, and tops contrasted sharply against the deep blue backdrop. Not a single prop (not even a chandelier) distracted the eye. The allegory of the beauty and aesthetic of 18th-century aristocratic life represented in Divertimento No.15 lies solely in the dance.

Its solos, pas de deux, and group sequences are intended only to be decorative (especially the symmetric tableaux embellished by ornamental arms) and require matter-of-course ease and noble yet humble composure. Masayu Kimoto, Timoor Afshar, and Davide Dato (who admirably managed his variation’s ever-changing directions of motion) represented this noblesse, though some ballerinas will need time to meet the technical demands. Hyo-Jung Kang and Kiyoka Hashimoto were both fabulous, but Natalya Butchko tried too hard to be sweet, and the speed of her solo challenged her. Olga Esina sailed on top of the choreography but failed to make it her own, and Sonia Dvořák seemed too focused on positions rather than the dance in between. With some fine-tuning of the arm synchronicity, the corps will look like a picture book.

Its solos, pas de deux, and group sequences are intended only to be decorative (especially the symmetric tableaux embellished by ornamental arms) and require matter-of-course ease and noble yet humble composure. Masayu Kimoto, Timoor Afshar, and Davide Dato (who admirably managed his variation’s ever-changing directions of motion) represented this noblesse, though some ballerinas will need time to meet the technical demands. Hyo-Jung Kang and Kiyoka Hashimoto were both fabulous, but Natalya Butchko tried too hard to be sweet, and the speed of her solo challenged her. Olga Esina sailed on top of the choreography but failed to make it her own, and Sonia Dvořák seemed too focused on positions rather than the dance in between. With some fine-tuning of the arm synchronicity, the corps will look like a picture book.

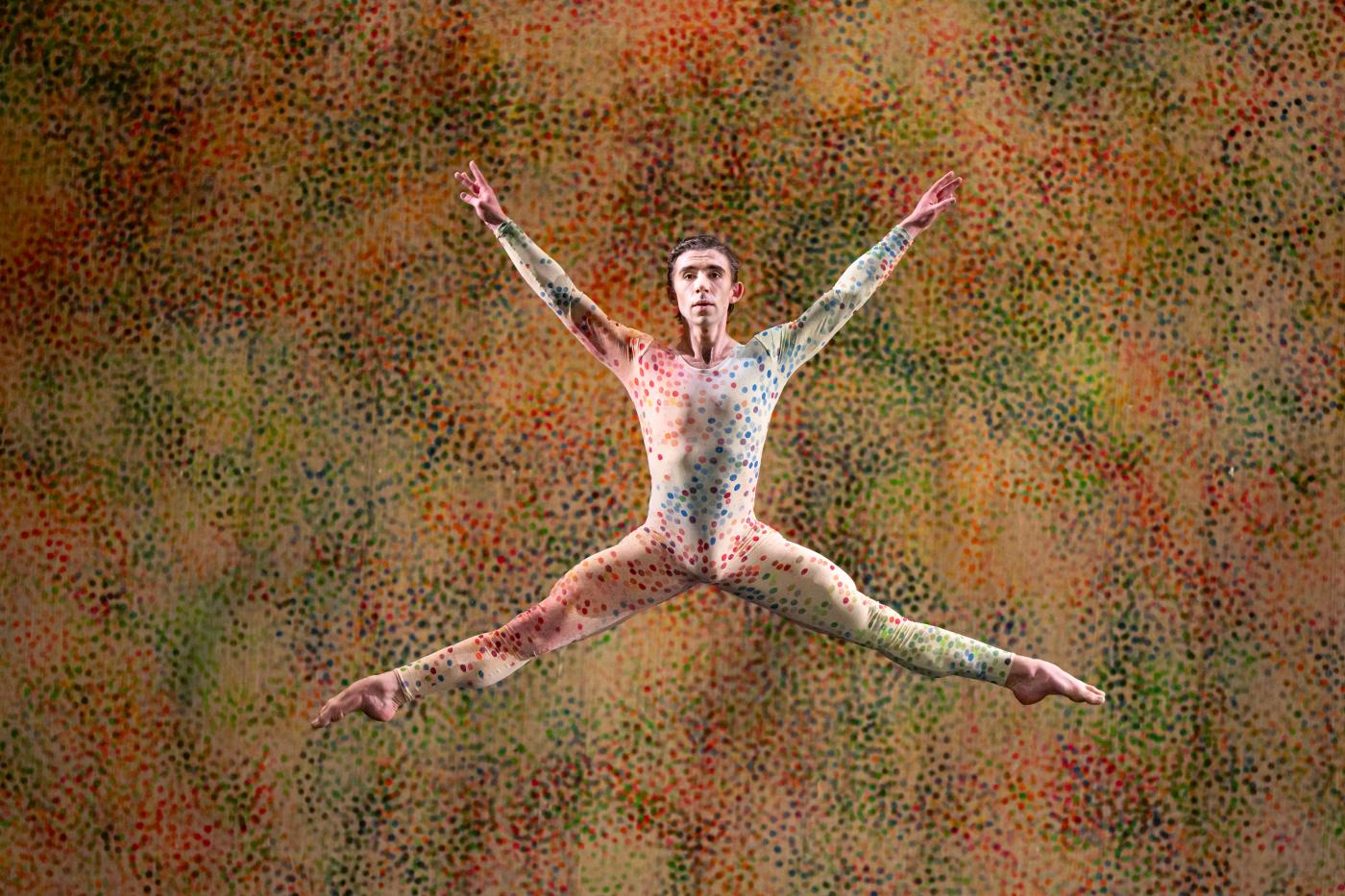

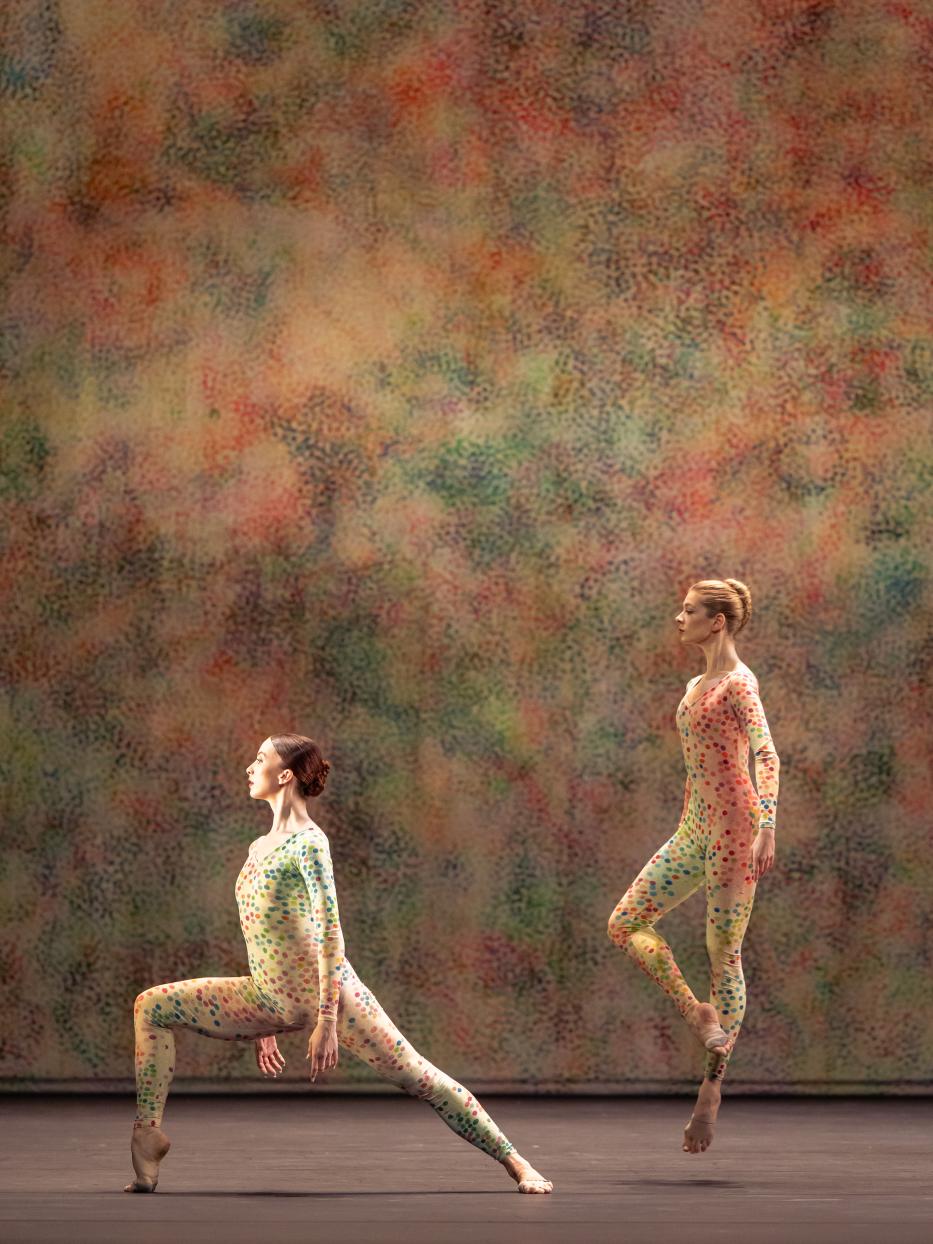

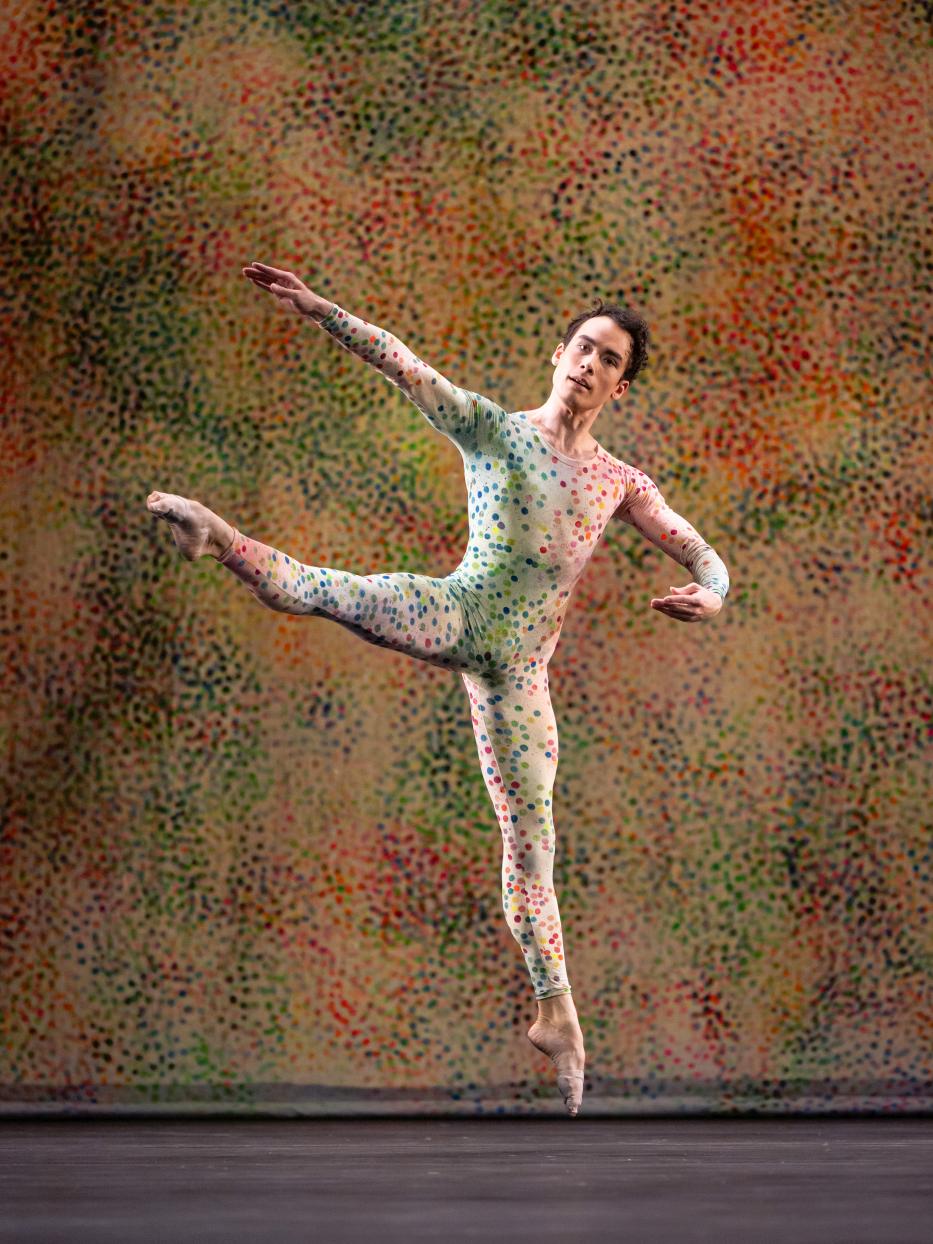

Perhaps Robert Rauschenberg was inspired by spots of light and shadow in a broadleaf forest on a sunny summer afternoon when designing the set and costumes of Summerspace (1958). He covered the backdrop and the dancers’ white tricots with colored dots akin to pointillism. The technique goes hand in hand with Cunningham’s approach to dance. The “dots” of his pieces—dance, music, costumes, and lighting—evolved independently like a laboratory construct and were assembled only at the actual performance. To what extent they built unity depended on the perception of the onlooker. It’s like dissecting the art of dance into its parts like a molecule into atoms, throwing the atoms back into the test tube, and waiting for them to reassemble. Cunningham’s style represents a side branch in the evolution of dance whose sap dried up.

Perhaps Robert Rauschenberg was inspired by spots of light and shadow in a broadleaf forest on a sunny summer afternoon when designing the set and costumes of Summerspace (1958). He covered the backdrop and the dancers’ white tricots with colored dots akin to pointillism. The technique goes hand in hand with Cunningham’s approach to dance. The “dots” of his pieces—dance, music, costumes, and lighting—evolved independently like a laboratory construct and were assembled only at the actual performance. To what extent they built unity depended on the perception of the onlooker. It’s like dissecting the art of dance into its parts like a molecule into atoms, throwing the atoms back into the test tube, and waiting for them to reassemble. Cunningham’s style represents a side branch in the evolution of dance whose sap dried up.

In Summerspace, the movements of the four women and two men were calculated according to the stage’s architecture. Its six entries allowed for twenty-one options to enter and leave. The order, tempo, and style of each performance was determined at random. The dancers were meant to portray birds, and their running, hopping, casual walking, deep pliés, slow arabesques, sudden stops, rotating and fluttering hands, and abrupt head movements were faintly reminiscent of such. Sometimes, they interacted standing back-to-back or courted and chased one another. Most of the time though, each danced for his or herself. Emotional expression was absent.

In Summerspace, the movements of the four women and two men were calculated according to the stage’s architecture. Its six entries allowed for twenty-one options to enter and leave. The order, tempo, and style of each performance was determined at random. The dancers were meant to portray birds, and their running, hopping, casual walking, deep pliés, slow arabesques, sudden stops, rotating and fluttering hands, and abrupt head movements were faintly reminiscent of such. Sometimes, they interacted standing back-to-back or courted and chased one another. Most of the time though, each danced for his or herself. Emotional expression was absent.

The piano music (composed by Morton Feldman and played by Milica Zakić and Johannes Piirto) comprised single tunes that fell like raindrops, sometimes assembled into partly harmonious, partly dissonant melodies, and intensified the feeling that the proceedings were irrelevant.

The piano music (composed by Morton Feldman and played by Milica Zakić and Johannes Piirto) comprised single tunes that fell like raindrops, sometimes assembled into partly harmonious, partly dissonant melodies, and intensified the feeling that the proceedings were irrelevant.

Schläpfer denies that choosing just Tchaikovsky’s poignant last symphony, Pathétique, was related to his farewell as artistic director. Doing so would be naive and immature, he said. But the final accompaniment—George Frideric Handel’s aria, Sweet Silence, Gentle Spring—Schläpfer added suggests otherwise.

The soul itself will be gladdened, when I, after this time of laborious futility, this peace I will see that awaits us in eternity,” soprano Florina Ilie sang. At this point, Marcos Menha (who already danced under Schläpfer at the Ballett am Rhein), lying on the floor like a cadaver after suffering terminal convulsions, was reawakened by the sprite-like Yuko Kato (also one of Schläpfer’s favored dancers who followed him from Düsseldorf).

The soul itself will be gladdened, when I, after this time of laborious futility, this peace I will see that awaits us in eternity,” soprano Florina Ilie sang. At this point, Marcos Menha (who already danced under Schläpfer at the Ballett am Rhein), lying on the floor like a cadaver after suffering terminal convulsions, was reawakened by the sprite-like Yuko Kato (also one of Schläpfer’s favored dancers who followed him from Düsseldorf).

The reason for Menha’s interim death was unclear. Wearing a low-cut, black pantsuit that glittered like a Hollywood outfit, he balanced across the stage as if crossing a river, cautiously stepping from one stone to the next. It would be a stretch to consider him an alter ego of Schläpfer, though the thought seems natural.

Enigmatic throughout, some scenes of Pathétique highlighted ballet history as seen through a distorted lens. Elena Bottaro, wearing an apricot dress with accordion pleats that made each développé an eyecatcher (costumes by Catherine Voeffray), was reminiscent of Princess Aurora. But she also abandoned her suitor (Arne Vandervelde) as Giselle did with Albrecht when disappearing with quick Bourres. Bottaro later swapped Vandervelde for Géraud Wielick, whose shiny outfit indicated a high rank.

Enigmatic throughout, some scenes of Pathétique highlighted ballet history as seen through a distorted lens. Elena Bottaro, wearing an apricot dress with accordion pleats that made each développé an eyecatcher (costumes by Catherine Voeffray), was reminiscent of Princess Aurora. But she also abandoned her suitor (Arne Vandervelde) as Giselle did with Albrecht when disappearing with quick Bourres. Bottaro later swapped Vandervelde for Géraud Wielick, whose shiny outfit indicated a high rank.

One woman kicked and stepped as if she were Carabosse and her legs were long nails. A man in black, latex pants contorted his limbs awkwardly while doing a headstand. Jackson Carroll hunched his shoulders, his wrists strangely kinked, like Quasimodo; Sveva Gargiulo clenched her hands in desperation before bypassing dancers hung pointe shoes onto each of her outstretched hands. She swung them like Poi balls before walking off stage with a vacant stare. Schläpfer briefly quoted Hans van Manen, whereas the twitching limbs and some jerky moves seemed borrowed from Marco Goecke.

One woman kicked and stepped as if she were Carabosse and her legs were long nails. A man in black, latex pants contorted his limbs awkwardly while doing a headstand. Jackson Carroll hunched his shoulders, his wrists strangely kinked, like Quasimodo; Sveva Gargiulo clenched her hands in desperation before bypassing dancers hung pointe shoes onto each of her outstretched hands. She swung them like Poi balls before walking off stage with a vacant stare. Schläpfer briefly quoted Hans van Manen, whereas the twitching limbs and some jerky moves seemed borrowed from Marco Goecke.

Urgency and suffering characterized the atmosphere of Pathétique from the start, but the female corps also faced one another aggressively as if clones of Lady Macbeth. The five dancers who drank themselves into oblivion later formed a guard of honor for a dancer who was pulled off stage on a simple cart. They held the empty bottles on top of their heads as if they were the spikes of their helmets.

Urgency and suffering characterized the atmosphere of Pathétique from the start, but the female corps also faced one another aggressively as if clones of Lady Macbeth. The five dancers who drank themselves into oblivion later formed a guard of honor for a dancer who was pulled off stage on a simple cart. They held the empty bottles on top of their heads as if they were the spikes of their helmets.

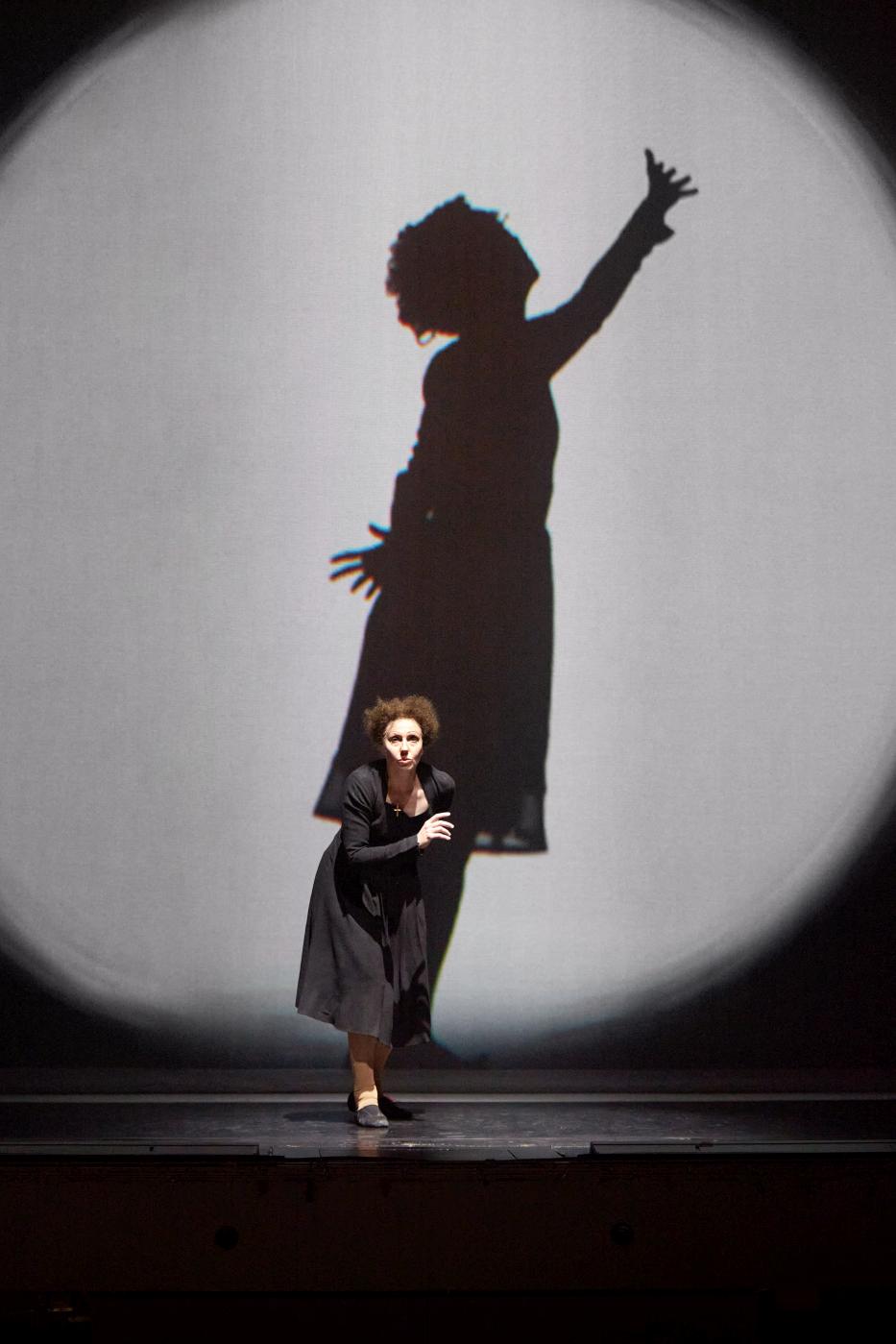

Thomas Mika’s set design resembled a huge, white poster that tattered into stripes when torn off. When lit from the side, these stripes and the beams of light formed a grid in which the dancers sometimes looked like otherworldly, ethereal beings. The set and lighting, together with the many scene changes and the mysterious plot, distracted from the fact that some sequences were showy fillers. What I missed, though, was emotional depth.

The Orchestra of the Vienna State Opera played Mozart’s and Tchaikovsky’s music under the baton of Christoph Altstaedt.

| Links: | Website of the Vienna State Ballet | |

| “Divertimento No. 15” – Rehearsal | ||

| “Summerspace” – Rehearsal | ||

| “Pathétique” – Rehearsal | ||

| Photos: | 1. | Ensemble, “Divertimento No. 15” by George Balanchine © George Balanchine Trust, Vienna State Ballet 2025 |

| 2. | Alisha Brach and ensemble, “Divertimento No. 15” by George Balanchine © George Balanchine Trust, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 3. | Hyo-Jung Kang and Davide Dato, “Divertimento No. 15” by George Balanchine © George Balanchine Trust, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 4. | Natalya Butchko and Masayu Kimoto, “Divertimento No. 15” by George Balanchine © George Balanchine Trust, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 5. | Masayu Kimoto, Davide Dato, Sonia Dvořák, and Hyo-Jung Kang; “Divertimento No. 15” by George Balanchine © George Balanchine Trust, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 6. | Hyo-Jung Kang and Davide Dato, “Divertimento No. 15” by George Balanchine © George Balanchine Trust, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 7. | Kiyoka Hashimoto and Davide Dato, “Divertimento No. 15” by George Balanchine © George Balanchine Trust, Vienna State Ballet 2025 |

|

| 8. | Sveva Gargiulo, “Summerspace” by Merce Cunningham, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 9. | François-Eloi Lavignac, “Summerspace” by Merce Cunningham, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 10. | Sveva Gargiulo and Eszter Ledán, “Summerspace” by Merce Cunningham, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 11. | Rebecca Horner, “Summerspace” by Merce Cunningham, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 12. | Jackson Carroll, “Summerspace” by Merce Cunningham, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 13. | Ensemble, “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 14. | Claudine Schoch, “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 15. | Natalya Butchko, Phoebe Liggins, and ensemble; “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 16. | Duccio Tariello, Gaia Fredianelli, Céline Janou Weder, Phoebe Liggins, and Andrés Garcia Torres; “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 17. | Elena Bottaro and Masayu Kimoto, “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 18. | Yuko Kato, Duccio Tariello, and ensemble; “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 19. | Sveva Gargiulo, “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 20. | Jackson Carroll and ensemble, “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| 21. | Ensemble, “Pathétique” by Martin Schläpfer, Vienna State Ballet 2025 | |

| all photos © Vienna State Ballet/Ashley Taylor | ||

| Editing: | Kayla Kauffman |